For those seeking more ammunition for their battery of anti-death-penalty arguments, look no further. “Anatomy of Injustice: A Murder Case Gone Wrong’’ is Raymond Bonner’s accomplished and meticulously researched investigation into a murder case that, as the clumsy title suggests, was egregiously bungled.

Me, the New York Times and D&D

I wrote this feature story for the New York Times Books section "In a Chaotic World, Dungeons & Dragons Is Resurgent: The role-playing game has made a surprising return to mainstream culture." (published online Nov. 13, 2019; on print Nov. 15).

In The Adventure Zone

I was thrilled to be part of this event to launch The Adventure Zone: Here There Be Gerblins, the graphic novel adapted from The Adventure Zone comedy and adventure podcast (based loosely on D&D). Brothers Justin, Travis, and Griffin McElroy, and father Clint McElroy, were in Boston at the Wilbur Theater July 19th, 2018, and I was there to interview them/moderate their on stage antics. Thanks for inviting me!

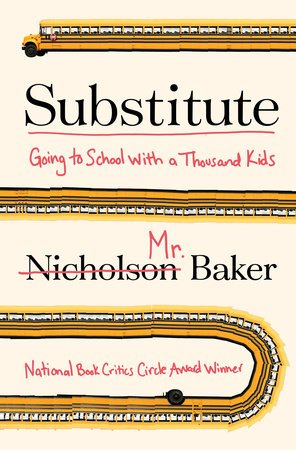

Nicholson Baker and “Substitute: Going to School With a Thousand Kids”

Nicholson Baker --- “Vox,” “The Fermata,” and “Human Smoke” -- has a new book called “Substitute: Going to School With a Thousand Kids,” which chronicles his stint substitute teaching in Maine’s elementary, middle and high schools. I get a chance to talk to Baker about his book for the Boston Globe.

Nicholson Baker --- “Vox,” “The Fermata,” and “Human Smoke” -- has a new book called “Substitute: Going to School With a Thousand Kids,” which chronicles his stint substitute teaching in Maine’s elementary, middle and high schools. I get a chance to talk to Baker about his book for the Boston Globe.

Headline: Nerd appears at TedX

Excited to appear at TEDxPiscataquaRiver in Portsmouth NH on May 6 alongside illustrious fellow speakers Steve Almond, Maxine Bédat, Zand Martin, Tina Nadeau, Jeff Sharlet, Skylar Bayer, Jennifer Dunn, Robert Eckstein, Muskan Kumari, amd Sam Rosen. My talk will be (something like) “How Dungeons & Dragons Makes You a Better Person.”

What is it like to run the Iditarod?

What it's like to run the Iditarod? In my story “1 woman, 16 dogs, and 1,000 miles of snow” for the Boston Globe, I interview Debbie Clarke Moderow about her dogsledding quest to finish the 1,000 mile race --- and write a book about it, called “Fast Into the Night: A Woman, Her Dogs, and Their Journey North on the Iditarod Trail."

Star Wars -- Shakespeare Mashup: A Review of Ian Doescher’s ‘William Shakespeare’s Tragedy of the Sith’s Revenge’

In “The Empire Strikes Back,” Yoda admonishes his apprentice, Luke Skywalker, saying, “Wars not make one great.” Later, in “Return of the Jedi,” he quips, “When 900 years old you reach, look as good you will not.”

In “The Empire Strikes Back,” Yoda admonishes his apprentice, Luke Skywalker, saying, “Wars not make one great.” Later, in “Return of the Jedi,” he quips, “When 900 years old you reach, look as good you will not.”

In case you didn’t catch on, Yoda inverts his syntax. In other words, Yoda practically speaks Shakespearean.

And in Ian Doescher’s best-selling “Star Wars” / Shakespeare mash-ups, so does every character in George Lucas’s science-fictional universe of Wookiees, droids and the Force.

Computer games can save your life

All part of the NYTBR's coverage of nerdy/comics/gaming books.

Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks Released in Brazil as "Tudo que um Geek deve saber"

I'm thrilled to announce that my book Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks is available in Brazil as Tudo que um Geek deve saber (All a geek should know). Read a sample chapter, in Brazilian Portuguese, here. And it looks like you can order it online here. (Someone, help me with the translation.) Thanks to Novo Conceito for publishing the book. Obrigado!

Book Picks on WGBH

Um, how terrifying is TV? Not so bad, once you're on camera. And the time just flies.

Um, how terrifying is TV? Not so bad, once you're on camera. And the time just flies.

I'm late to posting this, but I appeared before Xmas on WGBH's Greater Boston back in December.

Um, how terrifying is TV? Not so bad, once you're on camera. And the time just flies.

I'm late to posting this, but I appeared before Xmas on WGBH's Greater Boston program with Andre Dubus (House of Sand and Fog) and Marianne Leone (Jesse, a Mother’s Story). We discussed our holiday book selections.

Watch below, or get the video plus text of our book picks right on the WGBH site.

Huff Post "14 Holiday Gifts For Any Middle-earth Lover's Library" includes Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks

I am honored to be in the company of these other fine books. The post says Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks is "a moving and funny look at the saving grace and inspirational power of fantasy."

Great news today! Huffington Post named Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks one of "14 Holiday Gifts For Any Middle-earth Lover's Library."

I am honored to be in the company of these other fine books. The post says Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks is "a moving and funny look at the saving grace and inspirational power of fantasy."

and:

"Journalist Ethan Gilsdorf travels around the world on a poignant and hilarious quest to rediscover his youthful love of fantasy role playing games and Tolkien. He explores Oxford, England (where Tolkien taught and wrote most of his books), Marquette University in Wisconsin (where he gets to hold manuscript pages from The Lord of the Rings) and New Zealand (visiting the locations where the film trilogy was shot). It's a moving and funny look at the saving grace and inspirational power of fantasy."

Thanks so much, Huff Post. Read more.

Red Sox beards vs. Dwarf beards from The Hobbit

Who is Fili and who is Napoli? Balin vs. Buchholz? Ori or Ortiz?

Here's a "Beard Blueprint" --- my guide to the Red Sox vs. Hobbit dwarf beards.

According to The Hobbit, Thorin Oakenshield, head honcho of the dwarven company, had the longest beard. He also wore a sky blue hood with a large silver tassle. On the World Champion of American and Canada Red Sox squad, known to wear Navy blue war helmets and caps, I'd give Fullest Beard Award to Mike Napoli, Grayest and Wisest Beard to David Ross, Wildest Beard to Jonny Gomes and Creepiest Leprechaun Beard medal to Clay Buchholz. (For those making the Gandalf = Manager comparison, Sox skipper John Farrell resisted the urge to get all hirsute on us.)

Yes, these beards rule. But I can't help but think it's a shame that Ortiz wouldn't weave into his whiskers some silver or gold bling, or that Pedroia wouldn't let his grow into a great braided loop a la Bombur.

Note: Since this chart, some of the Sox beards have gotten even longer. And weider. And wilder.

A Review of Death Row Narrative "Anatomy of Injustice"

UPDATE TO THIS REVIEW: Edward Lee Elmore -- a black man who faced execution after he was wrongly convicted of killing a white woman in South Carolina -- was released from prison today after serving nearly thirty years. His release comes after numerous appeals and as the direct result of a plea deal negotiated by his attorney. Elmore's story is the subject of Raymond Bonner's new book ANATOMY OF INJUSTICE. Bonner, who was present at the Greenwood SC courthouse at the time of the announcement, said “It can hardly be called justice when, in order to obtain his freedom, a man had to plead guilty to a crime he did not commit.”

BOOK REVIEW

UPDATE TO THIS REVIEW: Edward Lee Elmore -- a black man who faced execution after he was wrongly convicted of killing a white woman in South Carolina -- was released from prison today after serving nearly thirty years. His release comes after numerous appeals and as the direct result of a plea deal negotiated by his attorney. Elmore's story is the subject of Raymond Bonner's new book ANATOMY OF INJUSTICE. Bonner, who was present at the Greenwood SC courthouse at the time of the announcement, said “It can hardly be called justice when, in order to obtain his freedom, a man had to plead guilty to a crime he did not commit.”

BOOK REVIEW

For those seeking more ammunition for their battery of anti-death-penalty arguments, look no further. “Anatomy of Injustice: A Murder Case Gone Wrong’’ is Raymond Bonner’s accomplished and meticulously researched investigation into a murder case that, as the clumsy title suggests, was egregiously bungled.

In 1982, in Greenwood, S.C., Edward Lee Elmore, 23, is accused of killing an elderly widow.

Elmore had occasionally done odd jobs for the victim. When her body is found in her closet, stabbed dozens of times and possibly raped, Elmore is fingered as the prime suspect, despite a notable lack of physical evidence linking him to the crime.

The small-town police officers, prosecutors, and medical examiners work together and cram his arrest, trial, conviction and eventual sentencing to death into three months - astonishingly rushed, given that most capital cases drag out for years. Elmore’s legal team is described as, at best, dispassionate, and at worst, incompetent. Bonner complains they did “virtually nothing.’’

Thickening the plot and heartbreak: The accused is poor, African-American, and mentally disabled, facts that seem never to bother the judges and juries over Elmore’s 27-year trail of legal appeals. He could not “tell time or draw a clock. He didn’t understand the concept of north, south, east, and west or of summer, fall, winter, and spring.’’ He could not do the elementary math to keep a bank account. Cross-examined on the stand, he simply replies, “I didn’t - ’’ “I couldn’t . . .’’ “No, sir, I wasn’t there.’’

A longtime reporter for The New York Times, where he shared a Pulitzer Prize, and a former New Yorker magazine staff writer, Bonner writes prose best described as workaday. It’s only in part two, when he introduces his narrative’s plucky heroine, Diana Holt, an idealistic lawyer with a sketchy criminal past who becomes Elmore’s guardian angel, does Bonner risk literary flourishes. “What the hell am I doing?’’ he has Holt thinking as she leaves Texas and her children behind to work at the South Carolina Death Penalty Resource Center. “Am I a horrible mother?’’

Holt makes a compelling protagonist. We invest in how, and if, she will get Elmore off death row. True-crime junkies also will be entertained by prurient details, from descriptions of the victim’s bludgeoned body to baggies of hair samples and blood-spattered jeans. We read transcriptions of courtroom proceedings, and we delight as witnesses are caught in lies. Neophytes to criminal law (this reviewer included) learn that despite new evidence proving a person’s innocence, fresh trials are rare. In this case, lawyers must prove not that Elmore was not the killer, but that his “constitutional rights had been violated.’’

If, voice-wise, “Anatomy of Injustice’’ can at times fall flat, as a piece of reporting, the book is masterful. Bonner builds the story, and his argument, carefully, rarely editorializing, mixing in a précis of capital punishment in the United States, and letting readers draw their own conclusions. And while Bonner’s investigation does not prove Greenwood’s law enforcement officials framed Elmore, he does make a convincing case that justice was not served. “Elmore’s story raises nearly all the issues that mark the debate about capital punishment: race, mental retardation, bad trial lawyers, prosecutorial misconduct, ‘snitch’ testimony, DNA testing, a claim of innocence.’’

Bonner’s book is an important addition to the body of evidence against the death penalty. As he argues, our system of justice thrives on conflict. In any trial, among the cast of conviction-seeking prosecutors and appellate lawyers hoping for a break, there must be winners and losers. “[T]he adversarial nature of it outweighs justice,’’ Bonner writes. “Justice often gets lost.’’

And while it would be unfair to reveal here whether Holt and Elmore win, beyond a shadow of a doubt it is worth reading “Anatomy of Injustice’’ to find out.

Memoir Recounts Youthful Quest for Meaning in D&D, Comics, Zeppelin

Growing up in the suburbs of Boston, and raised on secular Judaism, Cocoa Puffs and Gilligan’s Island, Peter Bebergal found himself on a quest. A spiritual quest that, as a teen, led him through comic books, Dungeons & Dragons and Carlos Castaneda, with stops in the world of hallucinogens, rock ‘n’ roll, and occultism. All were attempts to find a deeper, more meaningful path to personal illumination.

Growing up in the suburbs of Boston, and raised on secular Judaism, Cocoa Puffs and Gilligan’s Island, Peter Bebergal found himself on a quest. A spiritual quest that, as a teen, led him through comic books, Dungeons & Dragons and Carlos Castaneda, with stops in the world of hallucinogens, rock ‘n’ roll, and occultism. All were attempts to find a deeper, more meaningful path to personal illumination.

Bebergal’s new coming of age memoir, Too Much to Dream: A Psychedelic American Boyhood (Soft Skull Press) recounts that journey, using his own story and extensive research to explore the connections among popular culture, drugs, religion, and the craving for spirituality that America’s youth seeks, but rarely finds.

Bebergal is the also co-author of The Faith Between Us. He studied religion at Brandeis and Harvard Divinity School and writes frequently on the intersection of popular culture, religion, and science as well as reviews on science fiction and fantasy. Some of his essays and stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Tin House, Times Literary Supplement, Tablet Magazine, The Revealer, and The Believer. He lives in Cambridge, Mass., with his wife and son.

I had a chance to ask Peter Bebergal some questions — as well as happily geek-out on ’70s pop culture, D&D, Led Zeppelin and … wait for it … Freakies cereal.

Ethan Gilsdorf: Peter, why did you decide to write the book?

Peter Bebergal: At the age of 40, sober for many years, I found myself collecting psychedelic music again and reading counterculture/fringe spiritual texts, digging through the bins of underground comics at Million Year Picnic in Harvard Square. I realized that all these years later I was still drawn to this world. At the same time I started investigating and writing on the recent upsurge of psychedelic drug research and the burgeoning psychedelic subculture. I started to ask myself why my experiences led to where they had and despite them, why I still loved these ideas, this music, and these stories. I decided to investigate my own life and try to get beyond the traditional memoir by looking at myself as part of a particular cultural moment, the post ’60s generation who grew up in the shadow of that time.

Gilsdorf: What was so unique about the era of your coming-of-age?

Bebergal: The mid to late ’70s was a time of incredibly weird and wonderful fringe pop culture. You could buy ESP cards at any bookstore, Creepy and Eerie Magazine were part of a revival of horror and supernatural comics, In Search Of and books on UFOs were commonplace, but the undercurrent was a kind of spiritual dissociation. The Aquarian age never happened, but the doors of altered consciousness had been opened. There was no looking back. I began to understand how my own story was part of a much larger cultural moment. I was symptomatic of a kind of Phillip-K-Dickian-post ’60s spiritual schizophrenia.

Bebergal: The mid to late ’70s was a time of incredibly weird and wonderful fringe pop culture. You could buy ESP cards at any bookstore, Creepy and Eerie Magazine were part of a revival of horror and supernatural comics, In Search Of and books on UFOs were commonplace, but the undercurrent was a kind of spiritual dissociation. The Aquarian age never happened, but the doors of altered consciousness had been opened. There was no looking back. I began to understand how my own story was part of a much larger cultural moment. I was symptomatic of a kind of Phillip-K-Dickian-post ’60s spiritual schizophrenia.

Gilsdorf: As a kid also growing up in the same era, I remember being haunted by Leonard Nimoy’s In Search Of TV series, as well as devouring books about the Loch Ness monster and Bigfoot. There are tons of examples of the weird and occult breaking through in the ’70s to the mainstream, aren’t there? Think of the X-Ray Vision glasses you could order from the back of a comic book, or plans to build your own hovercraft, or spy cameras, ventriloquist dummies, all kinds of tricks and magic. Remember Freakies breakfast cereal? All about a post-hippie commune of misfit toys who lived in a tree. What was that about?

Bebergal: Freakies cereal is an amazing example of the fringe making it into the mainstream. But it was so giddily counterculture, almost like a hippie practical joke, and yet it seemed to have this deep mythology, replete with individual characters with their own personalities, and even the great mythic trope, a world tree where all the Freakies gathered. I had to have it! I recall it was hard to find though, and that it actually tasted kind of horrible, but they came with a terrific prize, a magnet in the likeness of one of the characters.

Gilsdorf: Yes, even to be a “freak” was celebrated, and money was to be made from that. I saved up whatever it was, 17 proofs of purchase from Freakies cereal boxes, to get my own “Snorkeldorf” T-shirt. There was a kind of vast commercialization of the unknown, of the weird and the unexplained. Big change from the 1960s, huh?

Gilsdorf: Yes, even to be a “freak” was celebrated, and money was to be made from that. I saved up whatever it was, 17 proofs of purchase from Freakies cereal boxes, to get my own “Snorkeldorf” T-shirt. There was a kind of vast commercialization of the unknown, of the weird and the unexplained. Big change from the 1960s, huh?

Bebergal: The end of the 1960s was the end of a grand narrative, one that was both political and spiritual, and that spoke to a young person’s rebellious instincts. By the 1970s all the ideas of the ’60s were now part of the popular imagination, and lost their edge, could no longer inspire the next generation in the same way, and church/temple hadn’t changed since the hippies showed the emperor had no clothes.

Gilsdorf: So where did one go from there, in the wake of this disillusionment?

Begergal: Many like myself turned to more fantastical narratives to fill the void. Marvel Comics, for example, contained an entire fully imagined universe. Characters from one comic appeared as guest stars in others, and their lives were linked by not only common cause, but by familial relationships, and strange genetic connections and mystical connections. The complex and cosmic Marvel Universe was all about the connections between one hero and another. I was obsessed with the Magneto/Wanda/Quicksilver family tree that also, inexplicably, involved the High Evolutionary [Editor's note: I didn't know who High Evolutionary was; turns out he's a superhero with extrasensory powers of clairvoyance, cosmic awareness and astral projection, among others. -- E.G.]

Gilsdorf: Somehow I missed drinking the superhero comic Kool-Aid. But I discovered D&D big-time. In Too Much to Dream, you talk about the connection between D&D and fantasy fiction and then the occult and psychedelics in your life. Can you explain it here?

Bebergal: I think D&D was the perfect early antidote to what had been an entire childhood filled with magical thinking and a kind of spiritual unease. D&D gave me a healthy channel to express these abstract feelings. It was a concrete manifestation of the imagination, but it had rules and structure. When I started reading the books about psychedelic experiences written in the ’60s, they were as wondrous and exciting as any D&D game or Silver Surfer comic, but they spoke to that deeper existential need. I put down my maps and rule books and picked up sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll.

Bebergal: I think D&D was the perfect early antidote to what had been an entire childhood filled with magical thinking and a kind of spiritual unease. D&D gave me a healthy channel to express these abstract feelings. It was a concrete manifestation of the imagination, but it had rules and structure. When I started reading the books about psychedelic experiences written in the ’60s, they were as wondrous and exciting as any D&D game or Silver Surfer comic, but they spoke to that deeper existential need. I put down my maps and rule books and picked up sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll.

Gilsdorf: Being a huge Led Zeppelin fan, I have to ask: Where does Tolkien and Zeppelin fit into all this?

Gilsdorf: Being a huge Led Zeppelin fan, I have to ask: Where does Tolkien and Zeppelin fit into all this?

Bebergal: In the ’60s and ’70s there was a resurgent interest in Tolkien. Publishers put out encyclopedias of his world, linking the books to this vast mythology that by the sheer immensity of detail felt somehow real and maybe even a little “true.” This is what happens to the richest kinds myths, how they take on a quality of truth. Even Led Zeppelin sang about Mordor as if it was place they had visited and returned from. And for all of this, the new phenomena of role-playing gave you the tools to act out these stories, to create new worlds drawing from Tolkien, comics, even rock ‘n’ roll music.

Gilsdorf: I love that idea that, in their music, Robert Plant and Jimmy Page were essentially role-playing characters who had gone on an adventure in Middle-earth, interacting with Black Riders and Gollum. Great concept. Any other musicians that did this? Styx? Kansas? Blue Oyster Cult?

Bebergal: That era was a wonderland of rock as hero quest. Styx sang about a great voyage by sea that turns into a journey into space, Kansas wrote about sky gods, prophecy and mystical insight, and my personal favorite Rush’s Farewell to Kings was an entire fantasy epic that ends with a journey into a black hole. And then of course there is the great 1970s science fiction band Hawkwind, who collaborated with and were inspired by Michael Moorcock.

Gilsdorf: What do you think makes some people look for meaning so desperately they are driven to the point of madness?

Bebergal: It starts with what is a fundamental part of the human experience. Religion and myth are attempts to contain this pursuit, to give it some symbols and ritual, to give it language. But for some people, the more structure you try to impose, the more they see it as an empty gesture, that God or whatever you want to call it cannot be contained by any hierarchy or imposed regulations. Occult or esoteric traditions are attempts to get beyond conventional wisdom to something more experiential, but in the modern world, they have become bound up with every kind of paranormal and fringe idea. Go into any New Age bookstore and conspiracy theories about Freemasons are on the shelf below Aleister Crowley, right next to the books on UFOs. Of course it can weigh you down. I have come to love this stuff with a bit more critical distance these days.

Gilsdorf: Have you ever thought, OK, all this spiritual stuff makes some sense, but maybe I just liked getting high?

Bebergal: This is, in many ways, the central question. There is no doubt that at the bottom of all this is my drug addiction. It ruled me for sure. But like all things, it too did not exist in a vacuum. All the expectations I had for what these substances would do for me were intimately tied into all things that drove my psychology; Fantastic Four comic books, the writings of Timothy Leary, the music of Pink Floyd. My expectations could never be met. I would always be let down, and therefore always be looking for the next high. At some point, though, that is all there was.

Gilsdorf: To me it seems geek culture — sci-fi, fantasy, gaming, etc. – is increasingly replacing traditional culture (church, parents, government, community) as a source of moral or spiritual guidance to a whole generation of folks. Think of the wisdom received not from priests but Yoda and Gandalf. Can you comment as to why this phenomenon exists?

Bebergal: I think that there is this amazing intersection between geek culture and Wiccan/pagan communities. Even geeks need spirituality, but continue to turn to non-traditional places to find it. These traditions also speak, of course, to an interest in the fictional worlds of magic and old gods, etc.

Gilsdorf: What lessons do we learn from geek culture?

Bebergal: I seek the divine now in more mundane places; playing Legos and Minecraft with my son, watching a heron take flight from an inlet on the Charles River, looking at Saturn’s rings and moons through a telescope, listening to John Coltrane.

Gilsdorf: What about gaming. Have you returned to the fold?

Bebegal: The truth is, I am playing D&D again these days, another attempt to recapture some of that adolescent adventure without the drugs. But never, I must say, without the rock ‘n’ roll!

Gilsdorf: Yes, and rocking out to Zeppelin, I hope. “So I’ve decided what I’m gonna do now | So I’m packing my bags for the Misty Mountains | Where the spirits go now, | Over the hills where the spirits fly | I really don’t know.” I’ll pack my bags too, and see you in Middle-earth.

For more information about Bebergal and his book Too Much To Dream, visit toomuchtodream.net.

Bebergal: I think the best recent example of this is the comic Hellboy, a devil spawn struggling to maintain his humanity and his goodness. His is the great lesson that we are more than our genes, more than our destiny even, be it familial, cultural, political. Most recently he had to sacrifice himself to save the earth. Pro sports and American Idol cannot tell this story. Only a comic book on cheap newsprint somehow has access to the deepest layers of myth and can make them modern and relevant.

Gilsdorf: Do you still crave mystical experiences? How do you access them?

Bebergal: At first I was worried any mystical search would lead me back to the self-destruction, but despite myself, in the years past I have had deep spiritual experiences. They did not singe the hair off my head, but they were profound and have been a reminder that our normal waking consciousness is capable of experiencing so much more. Whether or not psychedelic drugs are a positive catalyst for this, I cannot say. Some people, particularly those ingrained in traditions that use them as part of their religious rituals (the Native American Church for example), have found deep spiritual significance with them. All I know for sure is that they are not meant for me.

Gilsdorf: So where do you seek safer transcendental moments?

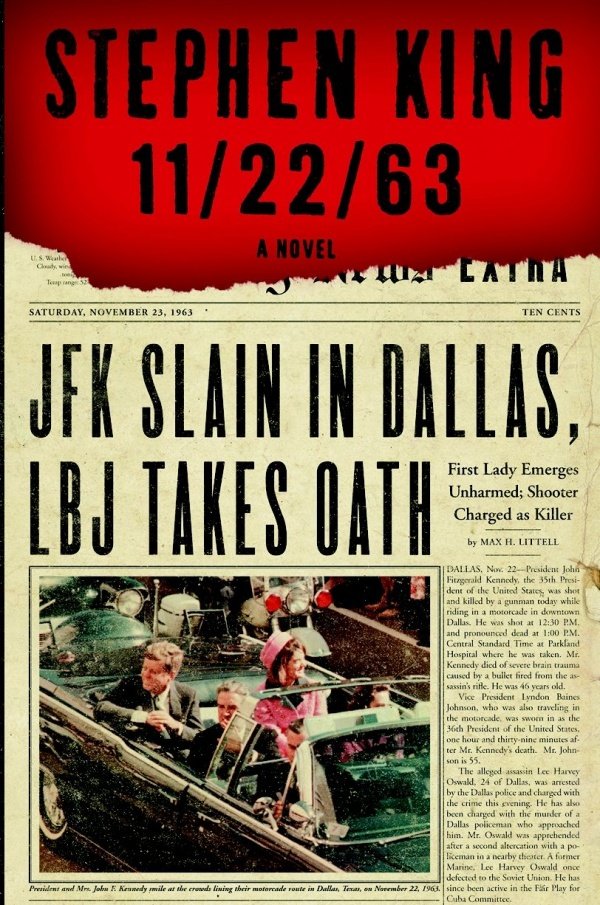

Change the past: A review of Stephen King's "11/22/63"

A review of "11/22/63"

A review of "11/22/63"

Time travel is tricky. Problem number one: You probably don't have a time machine parked in your garage. Not yet, anyway.

But let's assume you do. You rev up your metallic silver Chronos 1000. But the future doesn't interest you. You're tempted to visit the past. Because who can resist mucking with history? Nobody.

Depending on which rules of time travel are in effect, the outcome of your meddling will differ. If history is fixed and unchangeable, nothing happens. If alternate parallel histories can coexist, you may visit 1912, warn the Titanic's captain to watch for icebergs, and save those doomed passengers. Unfortunately, they'll still perish in the original timeline. Not a terribly satisfying save-the-day scenario.

Or as Stephen King posits in his new science fiction thriller "11/22/63," there's theory number three: history is flexible. Your backward travels can warp the course of future events (as long as you don't create a paradox, like challenging yourself to a duel).

King wonders what would happen if you time-trekked back to 1963 and killed the assassin before he got to President Kennedy. Would changing that watershed moment have prevented the country’s military escalation in Vietnam, saved the lives of RFK and MLK, yadda, yadda yadda -- in short, prevented many of the latter half of the 20th century’s ills? Those questions frame the basic premise of King’s book.

Assassinations and rifts in the space-time continuum are not foreign concepts to America’s King of Pulp. In “The Dark Tower’’ series, magical doors link far-flung worlds. In “The Dead Zone,’’ the clairvoyant protagonist shoots the president to avert nuclear Armageddon. Here, to kick-start the plot, King builds a wormhole in the pantry of a diner in Lisbon Falls, Maine. Like an express train, the time tunnel connects two destinations in history: the present and Sept. 9, 1958. Al, the diner’s tetchy proprietor, has been there and back a few times, mainly to buy hamburger at 54 cents a pound so he might sell 2011 burgers for $1.19. “Turns out I’m no longer tied to the economy the way other people are,’’ he jokes. Then Al finds a higher cause: Surveil Lee Harvey Oswald, determine whether he is the lone gunman, and take him out.

King ups the stakes with his own twists. Every visit back in time, no mat ter how long, takes only two minutes in the present. While in the past, travelers age normally. To accomplish his mission Al would need to go back to 1958 and stay five years. But his lung cancer would prevent him from lasting until 1963. The solution? Recruit Jake Epping, a 35-year-old high school English teacher, divorced, no children, and our first-person narrator. Jake takes up the quest, chucking his cellphone - “Keeping it would be like walking around with an unexploded bomb’’ - to live full time 53 years ago, pseudonymously as George Amberson. Jake/George soon discovers history is resistant to change, in direct proportion to the size of the event he wants to bend. “Obdurate’’ is the refrain. But the past can also be redeemed. If Jake kills Oswald and returns to 2011 to find the world ain’t better, a journey back restores history. “Every trip is the first trip,’’ Al says. “Because every trip down the rabbit-hole’s a reset.’’

The historical novel is already a well-established literary time machine, and King, who was 16 when JFK was shot, has done his homework, setting his characters on plausible collision courses with actual people and lovingly populating his “Land of Ago’’ with period details: drive-ins, pop songs, pep clubs, and finned convertibles. King balances his nostalgia on the cusp of tumult, just before this more naive world would be homogenized by television and strip malls and its smaller mind would wake up to racial injustice and military quagmire. As the author said in a recent interview, “11/22/63 was our 9/11.’’

No overt evil or supernatural presence haunts the novel, but buildings like an abandoned factory in Derry (a fictional Maine town readers of “It’’ and “Bag of Bones’’ will recognize) feel menacing. The Texas School Book Depository, where Oswald erects his sniper perch, emanates red-hot historical radiation. “The past harmonizes with itself,’’ Jake says, feeling more wraithlike than human. All through “11/22/63,’’ coincidences - often violent ones - ripple and accrue the longer Jake hangs around.

King’s thriller is full of suspense, and yes, you’ll want to know whether Jake gets to Dealey Plaza in time to stop the assassin’s bullet. If you’re not turned on by JFK conspiracy theories, the painstaking details of Oswald’s every move might feel tedious. You’ll also want to overlook how resourceful King makes his teacher, who conveniently knows about guns and surveillance techniques, and how to smooth-talk FBI agents.

Yet, uncharacteristic for Stephen King, a love story overshadows Jake’s creepy rendezvous with destiny. While in singular pursuit of Oswald, our hero settles in small-town Jodie, Texas, where he becomes a schoolteacher, falls for a clumsy librarian named Sadie, and starts accumulating his own cause-and-butterfly-effect. Helping a football player blossom into an actor, Jake/George finally sheds his ghostly trail - “It was when I stopped living in the past and just started living.’’ “11/22/63’’ ends up shining brightest as a metaphorical journey about “stupidity . . . and missed chances,’’ the perils of memory and regret, and the fantasy of starting over. To redeem America’s wounded psyche, Jake may or may not save the president. To redeem himself, he merely has to decide where to be present, and how to be present, in time.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of “Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms.’’ He can be reached at www.ethangilsdorf.com.

[this first appeared in the Boston Globe]

To reprint this or one of Ethan Gilsdorf's other articles, contact sales@featurewell.com or visit http://www.featurewell.com

Baroque, or bloated: My review of the new Neal Stephenson novel "REAMDE"

[Originally appeared in the Boston Globe]

[Originally appeared in the Boston Globe]

BOOK REVIEW

Techno thrills and gunplay, spelled out in great detail

Neal Stephenson’s “Reamde’’ opens with a target practice session at the Forthrast clan’s annual Thanksgiving gathering. Various firearms - shotguns, Glocks, assault rifles - are discharged into an Iowa pasture. Fun for the whole family.

The spasm of gunfire is prophetic. By the time Stephenson’s world-girdling novel has reached its exhaustive conclusion, countless rounds have been fired. As Stephenson notes in his acknowledgments, he required the services of a “ballistics copy editor’’ to fact-check the inner-workings of every Kalashnikov and bolt-action .22.

Stephenson is already notorious for churning out tomes sprawling in both page count and plot. But fans of his genre-blending touch that often welds historical to science fiction with a bead of cyberpunk might find themselves displeased with the ride of this narrative machine. Whereas “Snow Crash’’ and “Cryptonomicon’’ commingled code breaking, memetics, and nanotechnology with Sumerian myth, Greek philosophy, and economic theory, “Reamde,’’ set on present day planet Earth, barely traffics in such esoterica. Here, you’ll mostly find a techno-martial thriller, much in the same vein as Tom Clancy, albeit expertly crafted and often gorgeously written.

Richard is the dispassionate, outcast middle-aged brother of the Forthrast family who founded T’Rain, a World of Warcraft-like online fantasy game whose millions of devotees role-play mages and dwarves and build networks of vassals. Richard’s niece Zula, an Eritrean refugee and geoscientist, helps manage the virtual mineral deposits that players must “gold mine’’ to generate wealth. The MacGuffin? Zula’s cash-strapped, dimwit boyfriend bungles the black-market sale of stolen credit card data, which becomes corrupted by a virus called REAMDE, an anagram for “read me’’ - the file nobody reads when installing software. To restore the infected files, victims must deliver virtual ransoms to a “troll’’ (hacker), in the game. Meanwhile, bandits rob and kill these gold-ferrying avatars. Chaos rains down upon T’Rain.

When it’s determined the REAMDE hacker lives in China, the client for the data is none too pleased. That sets into motion Stephenson’s scenario tangling the fates of manifold characters: Russian mobsters, a Chinese tour guide, a British MI6 agent, a Hungarian techie, Islamic jihadists, and two Tolkienesque storytellers, among others. The action intercuts among these players who hop, skip, and jump vehicles, jets, and boats from the Pacific Northwest to China to the Rocky Mountains. Kidnappings trigger escape attempts. Plotlines collide. Bodies pile up.

This frenetic scope is tempered by Stephenson’s lingering pace. He tunes into the precise frequency of each character, how they process and remember stimuli, be they terrorist or innocent.

In one typical passage, Zula ruminates on the trauma of her capture, “shocked by how little effect it had on her, at least in the short term. She developed three hypotheses: 1. The lack of oxygen that had caused her to pass out almost immediately after she’d killed Khalid had interfered with the formation of short-term memories or whatever it was that caused people to develop posttraumatic stress disorder.’’ That’s just hypothesis number one.

Stephenson - a minimalist, he’s not - takes us deep in these warrens of thought, cause, and effect. (He resorts to awkward “exposition as dialogue’’ info dumps, too.) Moments are narrated with painstaking precision. The events of “Day 4’’ - a pitched battle among spies, mafia, extremists, and trolls, told from a kaleidoscope of perspectives - requires 200 pages. Decision tree huggers will revel in these tactics and processes; others will find the obsessive detail tedious.

Call “Reamde’’ baroque, or call it bloated. You decide.

The meat of the novel comes before the real-world gun-blazing begins: sly jabs at the war on terror, consumer culture, our online demeanor and misdemeanors, and insights into the shifts in consciousness that social and technological change have wrought. “[Y]ou kids nowadays substitute communicating for thinking, don’t you?’’, a Scotsman involved in the identity theft scheme complains. Walmart is likened to “a starship that had landed in the soybean fields,’’ and “an interdimensional portal to every other Walmart in the known universe.’’

These adroit touches may be enough to sustain readers caught in the crossfire. That said, Stephenson probably realizes that gunplay will gain the author new fans, while also losing him loyal legions of the old.

Ethan Gilsdorf, author of “Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks,’’ can be reached at www.ethangilsdorf.com. ![]()

Two New Books Lavish in 80s Video Game Culture

READY PLAYER ONE By Ernest Cline [Crown, 374 pp. $24.00]

READY PLAYER ONE By Ernest Cline [Crown, 374 pp. $24.00] SUPER MARIO: How Nintendo Conquered America, By Jeff Ryan [Portfolio, 292 pp., $26.95]It’s easy to cast a long shadow of nostalgia across your geeky past, now that you are standing taller.

SUPER MARIO: How Nintendo Conquered America, By Jeff Ryan [Portfolio, 292 pp., $26.95]It’s easy to cast a long shadow of nostalgia across your geeky past, now that you are standing taller.

There’s no shame, no risk of ridicule or reprisal, now that nerds top the food chain. More confident, you might even find yourself admitting, “Sure, I used to play Dungeons & Dragons. Had an 18th-level paladin named Argathon. One righteous orc-slaying dude.’’

I do. I played more than my share of video and role-playing games during a less friendly era, the 1980s. Fantasy and science fiction had not come out of the closet. The financial success of genre franchises had not yet made geekery acceptable. Gaming culture was nonexistent.

A bonus of my then fringe game habit: It felt user-driven, indie, even subversive. When free time, not money, was my currency, gaming created a peculiar, and intimate, community. I inserted real quarters into singular machines shared with others. No Internet. No interruptions from texts. Total immersion in virtual worlds was possible even as, paradoxically, cutting-edge special effects were analog, not digital.

And a game of Donkey Kong, its chunky graphics about as sophisticated as the dungeons I sketched on graph paper, might last only a minute, while a game of D&D, limited to the primitive technology of dice, pencils, and brainwaves, would take months.

Differing both in approach and success level, two new books -- Ernest Cline’s dystopian sci-fi novel “Ready Player One’’ and Jeff Ryan’s historical reportage “Super Mario: How Nintendo Conquered America’’ -- plumb and pay tribute to the genesis of our gaming culture. To a time when to find out who was the best at Asteroids or Galaga, you hoofed it down to the mall to witness the heroism gracing the “high score’’ screen, where someone’s tag -- “ZAK’’ or “LED’’ -- was hallowed only in the halls of your local arcade.

Ryan, a video game critic, painstakingly charts the Japanese company Nintendo’s startling success. When its 1980 Space Invaders rip-off Radar Scope failed, technicians retrofitted 2,000 of the machines with a new arcade game, designed by an underling named Shigeru Miyamoto. Donkey Kong was born, as was the character Mario, based on a real mustachioed landlord who once showed up at Nintendo’s US headquarters to collect the rent and “grew so incensed he almost jumped up and down.’’ The red overalls and hat came later.

Ryan, a video game critic, painstakingly charts the Japanese company Nintendo’s startling success. When its 1980 Space Invaders rip-off Radar Scope failed, technicians retrofitted 2,000 of the machines with a new arcade game, designed by an underling named Shigeru Miyamoto. Donkey Kong was born, as was the character Mario, based on a real mustachioed landlord who once showed up at Nintendo’s US headquarters to collect the rent and “grew so incensed he almost jumped up and down.’’ The red overalls and hat came later.

Ryan does a fine job describing Nintendo’s growing rivalry with Atari and Sega and subsequent shrewd moves, as arcades shuttered, to dominate the home console market. Super Mario Bros. became the “dense’’ game-changing killer app, Ryan writes, which “called for deep exploration instead of facile button mashing.’’ A new generation of gamers could explore endlessly, wandering tubes, hopping platforms, and collecting shells and coins. Nabbing the high score wasn’t the point. Mario helped kill quarter-based game culture.

Ryan can be insightful, and his prose colorful, but also distracting. Images and metaphors compete and clash - the Zucker Brothers follow Derrida, a music reference is slammed cheek-by-jowl with a baseball analogy. At times, the text seems translated from the Japanese. What is “a nebula’s improvement in graphics’’? A “veritable sleuth of unsold Teddy Ruxpins’’? It’s also difficult to picture the graphical evolution of Mario and his game world when the book has no illustrations.

Most frustratingly, we never hear directly from any Nintendo designers, not even Miyamoto or company head Hiroshi Yamauchi. Curiously little on-the-ground reporting of personal travails or internal corporate tensions. After the first 100 pages, the narrative devolves into a cheery laundry list of game releases. It’s as if Ryan reported the book from the distance of the Internet.

Still, “Super Mario’’ remains an important link to understanding how we got from Donkey Kong to Wii, and why the wee Jumpman still rules. “Mario is the id: working off of instinct, never having much of a plan, always able to leap into the middle of things. We all become younger as we play Mario, because when we’re Mario we simply play.’’

More so than Ryan, Cline banks on blatant nostalgia for our geeky pasts. The year is 2044 and the young protagonist of “Ready Player One,’’ 17-year-old orphan Wade Watts, narrates his own progress in an elaborate, online scavenger hunt. He lives as an economic refuge in a crime-ridden shanty town, “The Great Recession was now entering its third decade,’’ Watts says, and like many who have given up on the “real world,” he spends his waking hours as an avatar, named Parzival, in a massive, Matrix-like virtual space called OASIS.

Created by a reclusive, Reagan-era game designer, the game melds Tolkienesque riddles with ’80s pop arcana - from Matthew Broderick’s lines in “WarGames’’ to dungeons designed by D&D co-creator Gary Gygax. Solve the puzzles and you inherit the game designer’s vast fortune. An old-fashioned “high score’’ leader board pops up periodically in the narrative to remind us who’s winning.

Such is the post-apocalyptic, nerd-friendly premise of “Ready Player One.’’ Watts is one of thousands of other players known as “gunters,” or “egg hunters” because they are looking for Easter eggs, or clues, hidden in the thousands of designer virtual lands that populate the OASIS. Watts steeps himself in the period, eschewing the world of 2044 to effectively live and breathe the era’s most mundane factoids, memorizing characters from “The Breakfast Club,” plot points from “Star Wars,” tactics for an obscure arcade game like Joust. Clearly having fun with the reader, and himself, Cline stuffs his novel with a cornucopia of pop culture, as if to wink to the reader, “Remember the TRS-80? Wasn’t it cool?’’ The conceit is a smart one, and we happily root for Watts/Parzival and his gaming buddies on their quest for the big egg -- and hope they win before a villainous, corporate-run gaming guild declares “game over.’’

Not that the novel is without its problems. Cline, the screenwriter who gave us “Fanboys,’’ oddly chooses a first-person narrator. What is the occasion for a 17-year-old explaining the plot of “Blade Runner,’’ or that “ ‘2112,’ Rush’s classic sci-fi-themed concept album’’ hit record stores “in 1976, back when most music was sold on twelve-inch vinyl records’’? Long, awkward passages of exposition bog down the story, and conflict with Watts’s own distinctive narrative voice. A third-person, roving point of view would more logically allow for these passages of authorial intrusion. Also a bummer: Much of the action is virtual, statically describing Watts’s online moves: “I took a screenshot of this illustration and placed it in the corner of my display.’’

One can picture much of this working better on the big screen, where asides won’t be needed. We’ll hear “She Bop” on the soundtrack or see a character wearing a “Muppet Show” T shirt and get it. No surprise, Cline’s movie adaptation of Ready Player One has already been sold.

But ignore these narrative hiccups and “Ready Player One’’ provides a most excellent ride. Once the story is up and running, and the novel blasts to its world-ending climactic battle, I found the adventure story and its revenge of the dorks dream fully satisfying.

Both Cline and Ryan’s books lavish in the toys and pastimes of our youth. And also nostalgia, which may soft-focus the hard and real edges, and yet we're happy to lavish in it nonetheless. We aging humans traffic in it. Perhaps we must to make sense of our past lives.

Like the film “Super 8,’’ these two books play also into a final fantasy: that things were once simpler. Today, some attribute the violence in Norway, unfairly, to video games. Suddenly ’80s pop culture looks less troubled. But of course, the arcade and role-playing games of yore were controversial scourges bent on the destruction of youth. Remember?

16 books to buy the geek on your list

16 books to buy the geek on your list

Trouble finding the perfect last-minute gift for that geek on your shopping list? Here are 16 great books covering all stripes of geekery

Just in time .... a Geek Book Gift Guide

'Twas the night before Christmas, when through the black hole

Not a fanboy or girl was stirring, not even a troll;

The MacBooks were placed near the Wi-fi with care,

In hopes that St. Geekolas soon would be there.

Have you been a good little geek this year? Have you kept your PS3 and Xbox consoles all shiny and neat? Did you get all A’s in Elvish and Klingon and Shyriiwook (aka Wookiee Speak)? Did you roll all 20’s the last time you went dungeon crawling? If so, perhaps you’ll find one of these geek-eriffic books under the tree this year.

But if you haven’t been good ... Well, Sauron’s eye, I mean Santa’s eye, is ever watchful. So you better watch out.

My Best Friend Is a Wookiee: A Memoir, One Boy’s Journey to Find His Place in the Galaxy

by Tony Pacitti ($19.95, Adams Media)

Certified Star Wars geek (and Massachusetts native) Tony Pacitti charts his life in relation to the Trilogy—from pathetic childhood and adolescence to Luke Skywalker-like coming of age. We see a painfully shy kid slowly trying out the Jedi-like powers of adulthood and using the transformative Force (and forces) of the Star Wars universe to get him there. A hyperdrive tour through Star Wars fandom that's more fun than shooting womp rats in Beggar's Canyon. But “My Best Friend Is a Wookiee” also a comical, tender, no-punches-pulled coming of age memoir.

by Leo Tolstoy and Ben H. Winters ($12.95, Quirk Books)

What happens when you mash-up “Anna Karenina” with the world of 19th century Russia, this time retro-fitted with robotic butlers, mechanical wolves and moon-bound rocketships? You get “Android Karenina,” from the same folks who brought us “Pride and Prejudice and Zombies” and “Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters.” Here’s a sample line from Winters’ steampunked Tolstoy: “When Anna emerged [from the rocket], her stylish feathered hat bent to fit inside the dome of the helmet, her pale and lovely hand holding the handle of her dainty ladies’-size oxygen tank ...” A fun tongue-in-cheek romp for literature majors and science fiction aficionados alike.

We, Robot: Skywalker's Hand, Blade Runners, Iron Man, Slutbots, and How Fiction Became Fact

by Mark Stephen Meadows ($19.95, Lyons Press)

If you grew up like I did on a steady diet of “The Jetsons,” “The Six Million Dollar Man,” “Star Wars,” and “The Terminator,” then you’ve been wondering when all your robot fantasies might become true. But unlike personal jet packs (never happened) and hover craft (another back-of-comic-book pipe dream), cyborgs, androids, and avatars are real. With wit and insight, Mark Stephen Meadows separates science fiction from actual fact, navigating the ethically sketchy territory of domestic robots and autonomous military robots, artificial hands and artificial emotions. “We, Robot” raises the crucial questions that robot-makers largely ignore. In doing so, Meadows shows us that in our quest to create more and more life-like robots, we’ve become more robotic ourselves.

The Lord of the Rings Location Guidebook: Extended Edition

by Ian Brodie ($24.95, HarperCollins)

When I traveled to New Zealand to research my book “Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks,” and embarked on my own Lord of the Rings filming location geek-out quest, this guidebook was indispensable. With its detailed maps, directions, insider information and exclusive movie stills—even GPS coordinates—I was able to find dozens of sites, from the Shire (Matamata) to Mordor (Mt Ruapehu in Tongariro National Park) to Arrowntown’s The Ford of Bruinen, location for the famed “If you want him, come and claim him!” scene. Perfect for the Tolkien freak planning his or her own LOTR adventure Down Under.

Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter

by Tom Bissell ($22.95, Pantheon)

Must video games remain mere entertainment?Could they provide narratives that books, movies, and other vehicles for story delivery can’t? Might they even aspire to art? Tom Bissell's new book "Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter" aims a tentative mortar shot at these targets. His investigation is bedrocked upon personal experience; along the way, we also meet game developers at such megaliths as Epic Games, Bio Ware, and Ubisoft. Thankfully, the book isn’t pure fanboy boosterism. Video games can be great, he says, but they can be “big, dumb, loud.’’ A master prose stylist, the erudite Bissell is frequently insightful in the analysis of his video game obsessions.

![]()

Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games With God

by Craig Detweiler, editor ($19.95, Westminster John Knox Press)

A thoughtful collection of essays at the cross-section of religious and media studies. The various contributors take on quirky topics such as the theological implications of apocalyptic video games like Halo 3, Grand Theft Auto IV, and Resident Evil; how avatars are changing social networks and our spiritual lives; and the medical ethics and theology in controversial games such as BioShock. Bonus material includes an interview with Rand Miller, cocreator of Myst and Riven, and other video game industry folks.

by Dexter Palmer ($24.99, St. Martin’s Press)

In the steampunk tradition comes this debut novel a greeting card writer imprisoned aboard a zeppelin who must confront a genius inventor and a perpetual motion machine. In creating his world, Palmer borrowed from archival source materials that predicted life how life would be in the year 2000, then retro-designed modern gadgets that use turn-of-the-19th-century technology. A kind of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” as Jules Verne might have envisioned it and a great, richly-imagined read.

Confessions of a Part-Time Sorceress: A Girl's Guide to the Dungeons & Dragons Game

by Shelly Mazzanoble ($12.95, Wizards of the Coast)

Dungeons & Dragons insider Mazzanoble (she now works for Wizards of the Coast, the company behind D&D) gives a sassy and informative look at D&D from the female gamer's POV. She tackles myths and realities of gamer stereotypes and proves that women should be, and increasingly are, welcome to roll dice and at Cheetos with the rest of the trolls. As Mazzanoble writes: “Let’s get one thing straight: I am a girly girl. I get pedicures, facials, and microderm abrasions. I own more flavors of body lotions, scrubs, and rubs than Baskin Robbins could dream of putting in a cone. ... I am also an ass-kicking, spell-chucking, staff-wielding 134 year-old elf sorceress named Astrid Bellagio.”

Star Wars Jesus: A Spiritual Commentary on the Reality of the Force

by Caleb Grimes ($17.95, WinePress Publishing)

Is Obi-Wan Jesus? Why does Yoda speak like a character from the Old Testament? What inspires our devotion to this mythical universe of Jedis, Dark Sides and “feeling the Force”? Grimes gives us a different take on the LucasFilm empire, one that sees the Star Wars stories as potentially as powerful and useful as the ones we learned in Sunday school. In my case, I missed church entirely, but that didn’t stop me from quoting “There is no try. Do or do not” as a kind of spirtual/philosophical mantra.

Collect All 21! Memoirs of a Star Wars Geek: The First 30 Years

by John Booth ($14.95, Lulu.com)

Not long ago, enviro-spiritual interpretations of “The Lord of the Rings” were all the rage. Now, paeans to “Star Wars” are popular. Here’s one that’s a deliciously warped nostalgia trip through Star Wars fandom. From collecting Kenner action figures to getting Star Wars birthday cakes from puzzled parents to scribbling fan letters to Harrison Ford and Carrie Fisher, Booth shamelessly flaunts his lifelong lust for all things Star Wars. Like a tractor beam, this endearing account draws us in and makes us reminisce about our own geeky obsessions.

A Guide to Fantasy Literature: Thoughts on Stories of Wonder and Enchantment

by Philip Martin ($16.95, Crickhollow Books)

A diverse and thoughtful examination of the so-called “fantasy” genre: from Middle-earth to Narnia, high fantasy to dark fantasy, fairy-tale fiction to magic realism and adventure-fantasy tales. Peppered with meaty quotes by J.R.R. Tolkien, J.K. Rowling, C.S. Lewis and Stephen King, Martin’s book provides a concise primer for those wondering why it is we’re drawn to tales of magic quests and heroic derring-do.

The Mythological Dimensions of Doctor Who

by Anthony Burge, Jessica Burke and Kristine Larsen, editors ($15.00, Kitsune Books)

Dr. Who fans, rejoice! This collection of essays takes a look at the mythological undercurrent in this classic BBC television series considered by the Guinness World Records as the “longest-running science fiction television show in the world” and "most successful" science fiction series of all time.” (Take that, Lucas and Roddenberry). Topics connect Dr. Who to Arthurian legend, Batman and medieval Scandinavian Valkyries. An engaging discussion for the serious traveler of the Whoinverse.

Unplugged: My Journey into the Dark World of Video Game Addiction

by Ryan G. Van Cleave ($14.95, HCI)

Most of the time, playing video games is fine, fun and perfectly harmless. But every now and then, a player gets a little too immersed in a game’s imaginary word. In Cleave’s case, the game was World of Warcraft, and his playtime turned into an 80-hour-a-week, life-wrecking addiction. “Unplugged” tells a cautionary tale of hitting rock bottom, wising-up and climbing out of the dungeon.

How to Survive a Garden Gnome Attack: Defend Yourself When the Lawn Warriors Strike (And They Will)

by Chuck Sambuchino ($14.99. Ten Speed Press)

Silly. Ridiculous. And a hoot. In the spirit of those “how to survive a zombie apocalypse” manuals comes this tome to tell us how to defend against the latest enemy. The book claims it is “the only comprehensive survival guide that will help you prevent, prepare for, and ward off an imminent home invasion by the common garden gnome.” Great color photos bring the spoofy goofiness alive.

by Carl Warner ($22.50, Abrams Image)

For the food geek on your list. Sumptuous, jaw-dropping, eye-popping, mouth-watering fantastical landscapes made entirely from real fruit of this earth: vegetables, cheeses, breads, fish, meat, and grains (and fruit, too). The 25 photographs take you on a trip around the world... and the sweet treat is each photo is followed by making-of insights into the creative process. Don’t read on an empty stomach.

Geek Dad: Awesomely Geeky Projects and Activities for Dads and Kids to Share

by Ken Denmead ($17.00, Gotham)

The title pretty much says it all. You’re a geek. You have a kid who’s a geek (or you want to turn your kid into a geek). Read this crafty book for ideas to share your love of science, technology, gadgetry and MacGyver. Engineer and wired.com’s Geek Dad editor Ken Denmead offers projects so you and your child can, among other things: 1) launch a video camera with balloons; 2) make the "Best Slip n' Slide Ever”; and 3) build a working lamp with LEGO bricks and CDs. Soon, together, you can rule the galaxy as father and son. Mwahahah!

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, now in paperback. Follow his adventures and get more info on this book at /