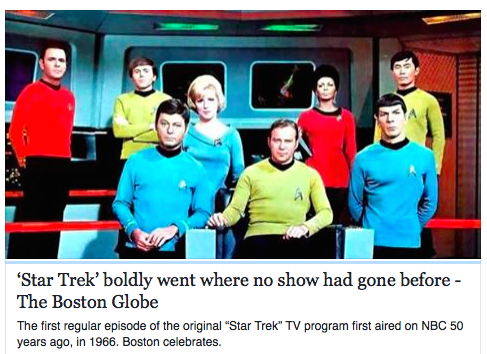

50 Years On, 'Star Trek' Fandom Continues To Prosper

Fifty years ago, "Star Trek" aired across the country Captain Kirk, Spock, Scotty and the crew of the Starship Enterprise. What's behind the franchise's enduring appeal, and why is Boston such a Trekkie haven? I appeared on WBUR's Radio Boston to discuss. Listen here.

William Shatner on “fandom frenzy” and 50 years of “Star Trek

In this story and Q&A for Salon, I speak to William Shatner about being "Forever Captain Kirk"; he opens up about “fandom frenzy” and 50 years of “Star Trek."

My Failure Is Complete: I Fell for Star Wars Hype. Now, Can We Just Watch the Damned Movie?

The hype-train has hit hyperdrive. The entertainment-industrial complex has devoured us all like that sarlacc from “Return of the Jedi” lurking in the Great Pit of Carkoon. This “Star Wars” fan is worn out: The nonstop marketing machine has turned fandom into a grind. Dear Lucasfilm and shareholders of the Walt Disney Co.: I just want to watch your damned movie. I wrote this rant for Salon.com. Enjoy!

The hype-train has hit hyperdrive. The entertainment-industrial complex has devoured us all like that sarlacc from “Return of the Jedi” lurking in the Great Pit of Carkoon. This “Star Wars” fan is worn out: The nonstop marketing machine has turned fandom into a grind. Dear Lucasfilm and shareholders of the Walt Disney Co.: I just want to watch your damned movie. I wrote this rant for Salon.com. Enjoy!Dune is in Your Head

If you've ever seen the 1984 David Lynch film version of Dune, or the three-part TV mini-series from 2000, you know that both adaptations of Frank Herbert's classic sci-fi novel left plenty of his world on the cutting room floor --- and left something to be desired.

If you've ever seen the 1984 David Lynch film version of Dune, or the three-part TV mini-series from 2000, you know that both adaptations of Frank Herbert's classic sci-fi novel left plenty of his world on the cutting room floor --- and left something to be desired.

But what if there was one version of Dune that would have blown the minds of critics before they had a chance to grumble?

In this story for BoingBoing, "Dune is in Your Head: The mirage of Jodorowsky’s Unfilmed Epic," I delve into the history of director Alejandro Jodorowsky's version of Dune, the one that was never made, and the one now captured in a terrific documentary called Jodorowsky's Dune.

Below, a couple of the production stills from the never realized film.

Concept art by Swiss artist H.R. Giger. All photos courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

Concept art by Swiss artist H.R. Giger. All photos courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

Storyboard of Dune, art by Jean Giraud, aka French comic book artist Moebius(Photo: David Cavallo) All photos courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

Storyboard of Dune, art by Jean Giraud, aka French comic book artist Moebius(Photo: David Cavallo) All photos courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

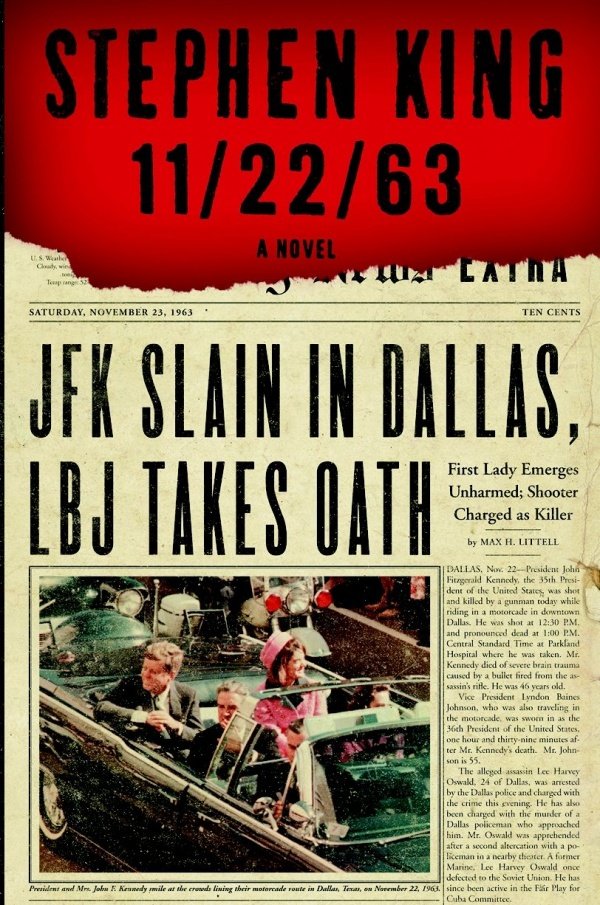

Change the past: A review of Stephen King's "11/22/63"

A review of "11/22/63"

A review of "11/22/63"

Time travel is tricky. Problem number one: You probably don't have a time machine parked in your garage. Not yet, anyway.

But let's assume you do. You rev up your metallic silver Chronos 1000. But the future doesn't interest you. You're tempted to visit the past. Because who can resist mucking with history? Nobody.

Depending on which rules of time travel are in effect, the outcome of your meddling will differ. If history is fixed and unchangeable, nothing happens. If alternate parallel histories can coexist, you may visit 1912, warn the Titanic's captain to watch for icebergs, and save those doomed passengers. Unfortunately, they'll still perish in the original timeline. Not a terribly satisfying save-the-day scenario.

Or as Stephen King posits in his new science fiction thriller "11/22/63," there's theory number three: history is flexible. Your backward travels can warp the course of future events (as long as you don't create a paradox, like challenging yourself to a duel).

King wonders what would happen if you time-trekked back to 1963 and killed the assassin before he got to President Kennedy. Would changing that watershed moment have prevented the country’s military escalation in Vietnam, saved the lives of RFK and MLK, yadda, yadda yadda -- in short, prevented many of the latter half of the 20th century’s ills? Those questions frame the basic premise of King’s book.

Assassinations and rifts in the space-time continuum are not foreign concepts to America’s King of Pulp. In “The Dark Tower’’ series, magical doors link far-flung worlds. In “The Dead Zone,’’ the clairvoyant protagonist shoots the president to avert nuclear Armageddon. Here, to kick-start the plot, King builds a wormhole in the pantry of a diner in Lisbon Falls, Maine. Like an express train, the time tunnel connects two destinations in history: the present and Sept. 9, 1958. Al, the diner’s tetchy proprietor, has been there and back a few times, mainly to buy hamburger at 54 cents a pound so he might sell 2011 burgers for $1.19. “Turns out I’m no longer tied to the economy the way other people are,’’ he jokes. Then Al finds a higher cause: Surveil Lee Harvey Oswald, determine whether he is the lone gunman, and take him out.

King ups the stakes with his own twists. Every visit back in time, no mat ter how long, takes only two minutes in the present. While in the past, travelers age normally. To accomplish his mission Al would need to go back to 1958 and stay five years. But his lung cancer would prevent him from lasting until 1963. The solution? Recruit Jake Epping, a 35-year-old high school English teacher, divorced, no children, and our first-person narrator. Jake takes up the quest, chucking his cellphone - “Keeping it would be like walking around with an unexploded bomb’’ - to live full time 53 years ago, pseudonymously as George Amberson. Jake/George soon discovers history is resistant to change, in direct proportion to the size of the event he wants to bend. “Obdurate’’ is the refrain. But the past can also be redeemed. If Jake kills Oswald and returns to 2011 to find the world ain’t better, a journey back restores history. “Every trip is the first trip,’’ Al says. “Because every trip down the rabbit-hole’s a reset.’’

The historical novel is already a well-established literary time machine, and King, who was 16 when JFK was shot, has done his homework, setting his characters on plausible collision courses with actual people and lovingly populating his “Land of Ago’’ with period details: drive-ins, pop songs, pep clubs, and finned convertibles. King balances his nostalgia on the cusp of tumult, just before this more naive world would be homogenized by television and strip malls and its smaller mind would wake up to racial injustice and military quagmire. As the author said in a recent interview, “11/22/63 was our 9/11.’’

No overt evil or supernatural presence haunts the novel, but buildings like an abandoned factory in Derry (a fictional Maine town readers of “It’’ and “Bag of Bones’’ will recognize) feel menacing. The Texas School Book Depository, where Oswald erects his sniper perch, emanates red-hot historical radiation. “The past harmonizes with itself,’’ Jake says, feeling more wraithlike than human. All through “11/22/63,’’ coincidences - often violent ones - ripple and accrue the longer Jake hangs around.

King’s thriller is full of suspense, and yes, you’ll want to know whether Jake gets to Dealey Plaza in time to stop the assassin’s bullet. If you’re not turned on by JFK conspiracy theories, the painstaking details of Oswald’s every move might feel tedious. You’ll also want to overlook how resourceful King makes his teacher, who conveniently knows about guns and surveillance techniques, and how to smooth-talk FBI agents.

Yet, uncharacteristic for Stephen King, a love story overshadows Jake’s creepy rendezvous with destiny. While in singular pursuit of Oswald, our hero settles in small-town Jodie, Texas, where he becomes a schoolteacher, falls for a clumsy librarian named Sadie, and starts accumulating his own cause-and-butterfly-effect. Helping a football player blossom into an actor, Jake/George finally sheds his ghostly trail - “It was when I stopped living in the past and just started living.’’ “11/22/63’’ ends up shining brightest as a metaphorical journey about “stupidity . . . and missed chances,’’ the perils of memory and regret, and the fantasy of starting over. To redeem America’s wounded psyche, Jake may or may not save the president. To redeem himself, he merely has to decide where to be present, and how to be present, in time.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of “Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms.’’ He can be reached at www.ethangilsdorf.com.

[this first appeared in the Boston Globe]

To reprint this or one of Ethan Gilsdorf's other articles, contact sales@featurewell.com or visit http://www.featurewell.com

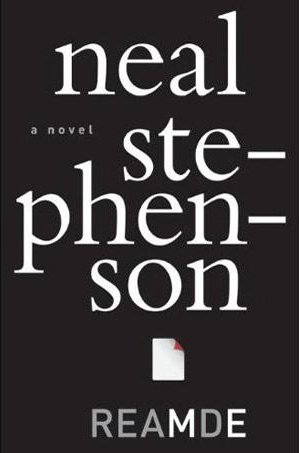

Baroque, or bloated: My review of the new Neal Stephenson novel "REAMDE"

[Originally appeared in the Boston Globe]

[Originally appeared in the Boston Globe]

BOOK REVIEW

Techno thrills and gunplay, spelled out in great detail

Neal Stephenson’s “Reamde’’ opens with a target practice session at the Forthrast clan’s annual Thanksgiving gathering. Various firearms - shotguns, Glocks, assault rifles - are discharged into an Iowa pasture. Fun for the whole family.

The spasm of gunfire is prophetic. By the time Stephenson’s world-girdling novel has reached its exhaustive conclusion, countless rounds have been fired. As Stephenson notes in his acknowledgments, he required the services of a “ballistics copy editor’’ to fact-check the inner-workings of every Kalashnikov and bolt-action .22.

Stephenson is already notorious for churning out tomes sprawling in both page count and plot. But fans of his genre-blending touch that often welds historical to science fiction with a bead of cyberpunk might find themselves displeased with the ride of this narrative machine. Whereas “Snow Crash’’ and “Cryptonomicon’’ commingled code breaking, memetics, and nanotechnology with Sumerian myth, Greek philosophy, and economic theory, “Reamde,’’ set on present day planet Earth, barely traffics in such esoterica. Here, you’ll mostly find a techno-martial thriller, much in the same vein as Tom Clancy, albeit expertly crafted and often gorgeously written.

Richard is the dispassionate, outcast middle-aged brother of the Forthrast family who founded T’Rain, a World of Warcraft-like online fantasy game whose millions of devotees role-play mages and dwarves and build networks of vassals. Richard’s niece Zula, an Eritrean refugee and geoscientist, helps manage the virtual mineral deposits that players must “gold mine’’ to generate wealth. The MacGuffin? Zula’s cash-strapped, dimwit boyfriend bungles the black-market sale of stolen credit card data, which becomes corrupted by a virus called REAMDE, an anagram for “read me’’ - the file nobody reads when installing software. To restore the infected files, victims must deliver virtual ransoms to a “troll’’ (hacker), in the game. Meanwhile, bandits rob and kill these gold-ferrying avatars. Chaos rains down upon T’Rain.

When it’s determined the REAMDE hacker lives in China, the client for the data is none too pleased. That sets into motion Stephenson’s scenario tangling the fates of manifold characters: Russian mobsters, a Chinese tour guide, a British MI6 agent, a Hungarian techie, Islamic jihadists, and two Tolkienesque storytellers, among others. The action intercuts among these players who hop, skip, and jump vehicles, jets, and boats from the Pacific Northwest to China to the Rocky Mountains. Kidnappings trigger escape attempts. Plotlines collide. Bodies pile up.

This frenetic scope is tempered by Stephenson’s lingering pace. He tunes into the precise frequency of each character, how they process and remember stimuli, be they terrorist or innocent.

In one typical passage, Zula ruminates on the trauma of her capture, “shocked by how little effect it had on her, at least in the short term. She developed three hypotheses: 1. The lack of oxygen that had caused her to pass out almost immediately after she’d killed Khalid had interfered with the formation of short-term memories or whatever it was that caused people to develop posttraumatic stress disorder.’’ That’s just hypothesis number one.

Stephenson - a minimalist, he’s not - takes us deep in these warrens of thought, cause, and effect. (He resorts to awkward “exposition as dialogue’’ info dumps, too.) Moments are narrated with painstaking precision. The events of “Day 4’’ - a pitched battle among spies, mafia, extremists, and trolls, told from a kaleidoscope of perspectives - requires 200 pages. Decision tree huggers will revel in these tactics and processes; others will find the obsessive detail tedious.

Call “Reamde’’ baroque, or call it bloated. You decide.

The meat of the novel comes before the real-world gun-blazing begins: sly jabs at the war on terror, consumer culture, our online demeanor and misdemeanors, and insights into the shifts in consciousness that social and technological change have wrought. “[Y]ou kids nowadays substitute communicating for thinking, don’t you?’’, a Scotsman involved in the identity theft scheme complains. Walmart is likened to “a starship that had landed in the soybean fields,’’ and “an interdimensional portal to every other Walmart in the known universe.’’

These adroit touches may be enough to sustain readers caught in the crossfire. That said, Stephenson probably realizes that gunplay will gain the author new fans, while also losing him loyal legions of the old.

Ethan Gilsdorf, author of “Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks,’’ can be reached at www.ethangilsdorf.com. ![]()

The Uncle in Carbonite

“What shall we draw?” I asked.

“Let’s draw Star Wars,” Jack said, innocently enough.

We began to draw Star Wars. Jack drew a guy, then a box. Next he drew a face and feet in the box. Then he made a line so the guy next to the box had an arm that touched the guy in the box.

“What the heck is that?” I asked.

“That’s me,” Jack said, adding his name to the figure on the left.

“So what is that?”

“How do you spell ‘carbonite’?” Jack asked, a big smile beaming across his face. He started to giggle.

“C-A-R …” I began. He began to write. The kid was seven. “B-O-N … I-T-E.” Then he added another word: “E-T-H-A-N-[space]-I-N.”

The giggling commenced.

“Wait. Is that me?”

More giggling from Jack.

I was incredulous. “You little … So, that makes you … Boba Fett?”

Uncontrollable giggling. “Uncle Ethan! You’re trapped in carbonite!”

Read the rest on wired.com's Geek Dad

What's up with alien invasion movies?

Battlefield: Earth

When alien visitors do not come in peace

The White House was one of several iconic sites destroyed by aliens in Roland Emmerich’s 1996 film, “Independence Day.’’ (20th Century Fox via AP)

The White House was one of several iconic sites destroyed by aliens in Roland Emmerich’s 1996 film, “Independence Day.’’ (20th Century Fox via AP)

Boston Globe Correspondent / March 11, 2011

“We’re facing an unknown enemy,’’ barks a Marine officer once the alien spacecraft have begun their assault in “Battle: Los Angeles.’’ In the film, which opens today, the attackers arrive in metallic ships. Other times, they arrive in asteroids, as in “The Day of the Triffids’’ (1962). Or they use asteroids as weapons: in “Starship Troopers’’ (1997) the Arachnids, or “Bugs,’’ from planet Klendathu launch a large space rock that flattens Buenos Aires.

But no matter the mode of transport, nothing gets our flags waving and patriotic juices flowing more than the threat of Earth’s destruction at the hands of ruthless, repugnant, anonymous aliens.

Here’s one reason: Because our angsty, modern-day wars don’t let us demonize the enemy as in decades past, it’s hard to get excited about blowing apart Iraqis and Afghans, whether in the real world or onscreen. Hence the appearance of “Battle: Los Angeles,’’ or last year’s LA-invasion “Skyline.’’ Combating hulking spacecraft and silvery foot soldiers whose weapons are surgically implanted ends up dicier than anything Al Qaeda can throw at us. In one scene, the platoon’s Nigerian medic grumbles, “[Expletive]! I’d rather be in Afghanistan.’’

Not all alien invasion movies are created equal. Earthlings might be mere bystanders in a battle between alien races: Take “Transformers’’ (2007) and its tagline “Their war. Our world.’’ Or “AVPR: Aliens vs Predator — Requiem’’ (also 2007). Watch “Invasion of the Body Snatchers’’ (1956, 1978) and you will notice the aliens don’t rub out metropolises; the Pod People colonize one citizen at a time. Or they walk unnoticed among us, as in “Men in Black’’ (1997). In the Godzilla “giant monsters’’ genre, or even “Cloverfield’’ (2008), they’re not even technically aliens, since the monsters (mostly) hatch from our atomic waste. The cartoon “Monsters vs. Aliens’’ (2009) combines these elements: A human beaned by a meteorite grows gigantic and joins forces with creatures to battle an invading alien robot.

You could argue these invasion films serve a higher cultural purpose. They can be seen as metaphors for some nameless fear — communism, viral infection, illegal immigration. Or think of these films as talismans. Directors imagine the worst, then the ruination won’t happen in real life.

But to paraphrase Gertrude Stein, “War is a war is a war is a war.’’

What follows are battlefield reports from a few memorable movies where the little green men invade armada-style in a coordinated attack, unilaterally and unprovoked. They storm the beaches of, say, Santa Monica, like it’s the Normandy invasion, ray guns a-blazin’. They harvest our resources, take no prisoners, and destroy our beloved strip malls and skyscrapers. When they do, we guiltlessly circle our wagons and fight back. As in “Battle: Los Angeles,’’ there’s only one rightful response. “You kill anything that’s not human.’’

“War of the Worlds’’ (1953, 2005)

You might say H.G. Wells’s 1898 book kick-started the whole alien-invasion genre. At least two major film adaptations (and one freaky radio broadcast) have followed, transposing the battleground from London to US cities. In the 1953 film version, the setting is Southern California. A meteorite falls, and out pop the manta-like Martian ships. A friendly greeting is answered by heat rays and electro-magnetic pulses that vaporize our backyards. Even our A-bombs are useless. When all hope seems lost, it turns out the aliens have no defense against our germs. Should have had their flu shots! Weirdly, 2005 gave us three remakes: two low-budget, straight-to-video affairs, and the Spielberg-Cruise megalith that takes us on a paranoid road trip from destroyed New York through the ravaged New England countryside to Boston, all the while the tripedal aliens hot on the refugees’ tails.

“Mars Attacks!’’ (1996)

Think of “The Day the Earth Stood Still’’ (1951, remade in 2008) or “Close Encounters of the Third Kind’’ (1977). An alien ship arrives. Do we strike first or parley? Do they talk back in musical tones or English? Do they play fair? In Tim Burton’s spoof starring a Hollywood who’s-who (Jack Nicholson, Annette Bening, Glenn Close, Jack Black, Natalie Portman, and more), the conventions are overturned. When Martians surround Earth with their flying saucers, negotiations begin. But the tricksy aliens infiltrate the White House and the destruction commences. The evil invaders even redo Mount Rushmore with Martian faces. Luckily, there’s always a weakness: This time their demise is Slim Whitman, whose yodeling voice in “Indian Love Call’’ causes alien brains to explode. Makes you want to place your K-tel order today.

“Independence Day’’ (1996)

The xenophobia and hawkishness of some of these invasion dramas aside, perverse pleasure can also be found in seeing beloved cities and monuments obliterated: the Eiffel Tower, White House, Golden Gate Bridge. That’s what we get in Roland Emmerich’s alien-inundation flick. Ragtag survivors gather in the Nevada desert in a last-ditch effort — on July 4 — to plan retaliation. But first the audience is treated to the deployment of dozens of 15-mile-wide saucers whose blue energy blasts decimate some of our favorite urban vacation destinations: DC, LA, New York. Eventually, a computer virus (not the common cold) defeats the ship’s force field, and Jeff Goldblum and Will Smith prevail. Yay, Earth!

Ethan Gilsdorf, author of “Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks,’’ can be reached at www.fantasyfreaksbook.com. ![]()

"Not so long ago, in a galaxy not so far, far away": Hanging with Nick Frost and Simon Pegg

from the feature story by Ethan Gilsdorf in the Boston Globe

Like Tolkien and Lewis, Nick Frost and Simon Pegg are British and longtime friends. Also like Tolkien and Lewis, Frost and Pegg tell stories that please them. “Paul,’’ the latest film they wrote and in which they star, opens Friday. It’s about two British geeks who leave the pop-cultural convention Comic-Con, in San Diego, on an RV excursion through the Southwest, only to take on an unexpected passenger: the title character, a gray-skinned, big-eyed, Area 51 escapee (voiced by Seth Rogen). Greg Mottola (“Adventureland,’’ “Superbad’’) directed.

“We’ve written a film that we want to watch and laugh at with our mates,’’ said Frost, in Boston last week to promote the film. Unlike the socially-awkward, aspiring science fiction writer Clive Gollings he plays in the film, the cheery Frost sported dark-rimmed glasses that self-consciously bespoke “nerd.’’ “That’s always what we have always done. You find that there are pockets of ‘us-es’ everywhere.’’

Those pockets of fanboys and fangirls will have a hard time not whispering to their theater seatmates when they spot the dozens of dorky inside jokes riffing off of “Star Wars,’’ “Star Trek,’’ “The X-Files,’’ “The Blues Brothers,’’ and nearly every fantasy or adventure film in the Steven Spielberg canon, from “Close Encounters’’ to “Raiders.’’

“The movie is very much a tribute to him,’’ said Frost, who was 10 when “E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial’’ was released in 1982; Pegg was 12.

Some of the references are more “sci-fi 101,’’ said Pegg, who plays Clive’s best friend, the wannabe comic book artist Graeme Willy. That’s to make sure average moviegoers and not just hardcore genre geeks will buy tickets. “We had to make this film appeal on a broad level because it cost a lot of money. Because of Paul, really. He’s expensive. It’s like hiring Will Smith, literally, to get Paul on the screen.’’

But Pegg promised the film has plenty of obscure references, too. “It’s replete with gifts for those who know their stuff,’’ he said. “For the faithful.’’

One such nod: “Duel,’’ an early Spielberg film, is listed in red letters on the movie marquee seen toward the end of “Paul.’’ “ ‘Easy Rider’ is on double bill with that,’’ said Frost. “The street we were [shooting] on was the street where Jack Nicholson meets Peter Fonda.’’ Be on the lookout for even more abstruse references, and cameos.

In fact, geeks might bring bingo cards that replace numbers with such items as “swooning Ewok,’’ “mention of Reese’s Pieces’’ “Mos Eisley cantina music (played by country band),’’ “dialogue from ‘Aliens,’ ’’ and “bevy of metal bikini-costumed, ‘slave girl’ Princess Leias.’’ Drinking coffee in a hotel suite overlooking the Charles River, the two stressed that the point of “Paul’’ was not to ridicule those who collect samurai swords or speak Klingon (as both characters do in the film), but to celebrate them.

“We never wanted to make fun of it,’’ said Pegg. “Obviously those kind of fans are our bread and butter and helped get us where we are. We didn’t want to then turn around and say ‘Ha, ha. You big bunch of losers.’ ’’ Clive and Graeme are portrayed as mildly, and endearingly, dysfunctional and codependent, but ultimately good guys with big hearts.

Both actor-writers long ago established their geek cred. Pegg costarred with Frost in the cop-action movie spoof “Hot Fuzz’’ (2007) and the “zomedy’’ “Shaun of the Dead’’ (2004). Pegg cowrote both films and more recently voiced the character Reepicheep in “The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.’’ “Young Scotty,’’ from “Star Trek’’ (2009), is his highest profile role to date. He will also star in the planned sequel. Both have acted in the forthcoming “Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn,’’ and when the Spielberg-Peter Jackson motion-capture juggernaut hits screens later this year, each of their stars will rise even higher into the dweeby firmament.

On the “Paul’’ set, they also geeked out on special effects required to bring the pot-smoking, wise-cracking space-dude to life. Rogen (“The Green Hornet,’’ “Knocked Up’’) shot a video reference version of the movie and recorded dialogue on a sound stage, but never joined the actors on location. Instead, Pegg, Frost, and the rest of the cast, which includes Jason Bateman and Kristen Wiig, acted with “a child, a small man, a ball, a stick with balls on it, some lights,’’ said Pegg. “All the way through I was thinking, this is never going to work.’’

Lining up sightlines between the eyes of humans and the yet-to-be generated CG Paul (to establish believable connections between the characters) caused the biggest headaches. “How do I know where to look?’’ Pegg said. “But it worked.’’ (“You see Ewan McGregor looking at Jar Jar Binks,’’ he added, taking a swipe at the “Star Wars’’ prequels. “He’s like looking above his head.’’)

If one geek fantasy is finally to defeat the bully, get the girl or boy, and find fame or fortune with your secret passion, then “Paul’’ fulfills the dream. Not to spoil the ending, but Willy and Gollings do become rock stars in their own realm.

Another holy grail is that geeks might get to hang with real wizards, orcs, hobbits, superheroes, or robots. For two hours, “Paul’’ brings this pipe dream closer, too.

“We always see these characters in fantasy environments. We see Gollums in Middle-earth and all the ‘Star Wars’ animations are in the ‘Star Wars’ universe,’’ said Pegg. “The context fits the sprite. But in ‘Paul,’ we wanted that character to be in an environment that was totally, literally, alien to him.

“And that makes him seem even more real, because you don’t expect to see him.’’

Ethan Gilsdorf, author of “Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks,’’ can be reached at www.fantasyfreaksbook.com. ![]()

Is steampunk the new goth?

Is steampunk the new goth?

By Ethan Gilsdorf, December 29, 2010

(links to images on the Christian Science Monitor site)

A Steampunk mantel clock by Roger Wood of Ontario is valued at $1,500. It’s part of an exhibition titled (with Steampunkish ornament), ‘Steampunk, Form and Function, an Exhibition of Innovation, Invention and Gadgetry’ at a Waltham, Mass., museum. [photo: Melanie Stetson Freeman/Christian Science Monitor Staff]Some pop culture genres such as Tolkienesque fantasy imagine a magical past of strange races and global quests. Others, such as hard-core dystopian science fiction, warn against a future marred by apocalyptic meltdown.

A Steampunk mantel clock by Roger Wood of Ontario is valued at $1,500. It’s part of an exhibition titled (with Steampunkish ornament), ‘Steampunk, Form and Function, an Exhibition of Innovation, Invention and Gadgetry’ at a Waltham, Mass., museum. [photo: Melanie Stetson Freeman/Christian Science Monitor Staff]Some pop culture genres such as Tolkienesque fantasy imagine a magical past of strange races and global quests. Others, such as hard-core dystopian science fiction, warn against a future marred by apocalyptic meltdown.

Then comes steampunk, a hybrid vision of a past that might appear in the future – or a future that resides, paradoxically, in the spirit of another age.

No, you're not stuck in some goofy concept album by The Moody Blues. Steampunk is a fantasy made physical, made of brass and wood and powered by steam, born of the Industrial Age and inspired by the works of H.G. Wells and Jules Verne. It takes form both as an aesthetic movement and a community of artists; role-players; visionaries; and those who use the tools of literature, film, music, fashion, science, design, architecture, and gaming to manifest their visions.

"[Steampunk is] drawing on actual history. You can pull into it what you're into and put your spin on it. It's accessible yet expandable," says Jake von Slatt (real name: Sean Slattery, of Littleton, Mass.), who likens the philosophy behind steampunk to the open-source software movement. "There is a real focus on sharing, exploring things together, building community."

Steampunkers gather in conventions to exchange ideas – plus, they know how to dress to the nines and party like it's 1899.

Mr. von Slatt, who came of age in the era of punk rock, new wave, and Goth, has always been a tinkerer. Steampunk lets him "revisit youthful enthusiasms," he says. Now he creates intricately crafted anachronistic objects: for example, computer keyboards taken apart and rebuilt with brass, felt, and keys from antique manual typewriters. He's transformed a 1989 school bus into a wood-paneled "Victorian RV," which he uses to travel to steampunk conventions.

Currently, he's "steampunking" a fiberglass, 1954-style Mercedes kit car, tricking it out with salvaged gauges and lights from other cars and gold filigree trim. Drawn to steampunk's "do-it-yourself, making something from nothing" mantra, von Slatt scavenges most of his components from the dump.

Roots in a 1960s TV series

Steampunk was first introduced as a literary subgenre. William Gibson and Bruce Sterling's 1990 novel "The Difference Engine" popularized the idea of an alternate history where the Industrial Revolution-level technology of pistons and turbines, not electricity, powers modern gadgets, as Victorians might have designed them. But even way back in 1960s, the television series "The Wild Wild West" helped define the genre. The sci-fi western featured a train outfitted with a laboratory and featured protagonists who were gadgeteers.

Today, steampunk's reach has exploded, from Boston to San Francisco's Bay Area, to Britain, New Zealand, Japan, and beyond.

"Steampunk is definitely growing in popularity," says Diana Vick, vice chair of Steamcon, an annual convention in Seattle that doubled its attendance when it held its second meeting in November. "I believe it is due in part to the fact that it is a rejection of the slick, soulless, mass-produced technology of today and a return to a time when it was ornate and understandable."

This year, Steamcon celebrated what its website called the Weird Weird West. It notes: "Imagine the age of steam on the wild frontier ... roughriders on mechanical horses, mad inventors ... mighty steam locomotives ... airships instead of stagecoaches."

Every culture that embraces steampunk seems to make it their own. Patrick Barry, a member of New Zealand's League of Victoria Imagineers, has seen myriad international examples. "All have a different flavour, world vision and cultural base for the artists and writers to draw from and it shows," he writes via e-mail. Even in his tiny hometown of Oamaru, steampunk has taken off. Three groups have recently mounted an exhibition, a fashion show, and run several events. "Oamaru has a population of about 13,000 people. We had 11,000 people visit the exhibition over its six week [run]."

Previously, most works in the genre would have been set only in the Industrial Age. Over time, explains Dexter Palmer, author of the novel "The Dream of Perpetual Motion," the term "steampunk" has undergone "definition creep." "Nowadays the label's much more comprehensive, and seems to refer to any retrofuturistic or counterfactual work that features machines with lots of gears, or lighter-than-air flying craft, or similar sorts of things."

Some works have been retroactively embraced as part of the genre. For example, Terry Gilliam's dystopian satire, "Brazil," is now considered steampunk even though the film was not called steampunk when it was released in 1985.

In Mr. Palmer's novel, a greeting-card writer who is imprisoned aboard a zeppelin must confront a genius inventor and a perpetual motion machine. The author created a set of rules for his fictional universe: While things might be "scientifically implausible" to the reader, they would be "self-consistent and plausible to the inhabitants of the imaginary world." He based his ideas on source materials that predicted life in the year 2000 and then designed gadgets that seemed modern, but used turn-of-the-century tech. For example, there's an answering machine in the novel that functions by recording to a wax cylinder.

'It wants to teach us things'

"One of the really wonderful things about Steampunk is that it, more than any other subculture, seems to want to teach us things," von Slatt wrote on his blog at steampunkworkshop.com. And, like the punk and Goth movements before it, steampunk teaches another way of looking at the world.

Ms. Vick adds that another appeal lies in its largely optimistic and romantic, not dark and cautionary, outlook. "We also embrace and foster good manners and dressing up, which are both sorely lacking in society today," she says.

Indeed, dedicated steampunkers are lured by fashion. To dress up as a privateer and pilot flying machines powered by "lift-wood," or play a mad scientist who meddles in alchemy, the required accouterments include corsets, top hats, and lace-up boots; military medals, parasols, and aviator goggles.

Bruce and Melanie Rosenbaum aren't particularly into costuming, but when attending an event they will break out period garb. Their businesses, ModVic and SteamPuffin, offer home remodeling and design services for steampunking Victorian-era homes, an idea they applied to their own 1901 house in Sharon, Mass. They loved the turn-of-the-century fantasy but, Bruce says, "you don't want to live in the 19th century in terms of conveniences." So they retrofitted modern appliances or hid them behind facades of functional art. Combining old and new, their living room sports a plasma TV framed by an antique wooden mantel.

Upstairs, Bruce's attic office incorporates portholes, a bank vault door, and computer workstation made from an antique desk and pipes from a pump organ. You can almost see the ghost of Jules Verne hammering out a few e-mails.

"How much more fun is it to make something ornate and beautiful, rather than boring and unadorned?" asks Melanie. The couple is working on a book project, and recently curated two exhibits in the Boston area.

Tom Sepe, an artist exhibiting in one of them, the "Steampunk Form & Function" show at the Charles River Museum of Industry & Innovation in Waltham, Mass., shipped his "Whirlygig," a "steam-electric-hybrid motorcycle," from his workshop in Berkeley, Calif. The circus performer discovered steampunk via the Burning Man art community, and looks at his life as art. "Every choice we make is part of a performance," he says. "Every object we make or touch becomes an artifact of who we are and how we have been."

For Mr. Sepe, "three crucial elements" keep him engaged in the steampunkmaker culture: the "warmth factor" of its handmade materials, its functionality, and whimsy – "free thinking imagination and fun." Unlike other art forms, he says, "It doesn't take itself too seriously."

And whereas other genre fans can niggle over the small stuff, steampunk tends to be more open-ended. Jeff Mach, one of the partners behind New Jersey's Steampunk World's Fair, remembers Goths back in the 1990s sniping at one another for not being "Goth enough." No so with this latest, more inclusive cultural mashup. "It's not starting from a single point but many points," he says.

Many suggest steampunk is the next Goth, or even bigger. "I think this is the beginning of steampunk as a new sort of thing, as a pop culture phenomenon," says von Slatt. "I think it's the tip of the iceberg."

Violent Video Games Are Good for You

[upcoming events with Ethan Gilsdorf: NYC/Brooklyn 11/22 (panel "Of Wizards and Wookiees" with Tony Pacitti, author of My Best Friend is a Wookiee); Providence, RI: 12/2 (also with Pacitti); and Boston (Newtonville 11/21 and Burlington 12/11) More info ...]

Violent Video Games Are Good for You

Rock and roll music? Bad for you. Comic books? They promote deviant behavior. Rap music? Dangerous.

Rock and roll music? Bad for you. Comic books? They promote deviant behavior. Rap music? Dangerous.

Ditto for the Internet, heavy metal and role-playing games. All were feared when they first arrived. Each in its own way was supposed to corrupt the youth of America.

It’s hard to believe today, but way back in the late 19th century, even the widespread use of the telephone was deemed a social threat. The telephone would encourage unhealthy gossip, critics said. It would disrupt and distract us. In one of the more inventive fears, the telephone would burst our private bubbles of happiness by bringing bad news.

Suffice it to say, a cloud of mistrust tends to hang over any new and misunderstood cultural phenomena. We often demonize that which the younger generation embraces, especially if it’s gory or sexual, or seems to glorify violence.

The cycle has repeated again with video games. A five-year legal battle over whether violent video games are protected as “free speech” reached the Supreme Court earlier this month, when the justices heard arguments in Schwarzenegger v. Entertainment Merchants.

Back in 2005, the state of California passed a law that forbade the sale of violent video games to those younger than 18. In particular, the law objected to games “in which the range of options available to a player includes killing, maiming, dismembering or sexually assaulting an image of a human being” in a “patently offensive way” — as opposed to games that depict death or violence more abstractly.

But that law was deemed unconstitutional, and now arguments pro and con have made their way to the biggest, baddest court in the land.

In addition to the First Amendment free speech question, the justices are considering whether the state must prove “a direct causal link between violent video games and physical and psychological harm to minors” before it prohibits their sale to those under 18.

So now we get the amusing scene of Justice Samuel Alito wondering “what James Madison [would have] thought about video games,” and Chief Justice John Roberts describing the nitty-gritty of Postal 2, one of the more extreme first-person shooter games. Among other depravities, Postal 2 allows the player to “go postal” and kill and humiliate in-game characters in a variety of creative ways: by setting them on fire, by urinating on them once they’ve been immobilized by a stun gun, or by using their heads to play “fetch” with dogs. You get the idea.

This is undoubtedly a gross-out experience. The game is offensive to many. I’m not particularly inclined to play it. But it is, after all, only a game.

Like with comic books, like with rap music, 99.9 percent of kids — and adults, for that matter — understand what is real violence and what is a representation of violence. According to a report issued by the Minister of Public Works and Government Services in Canada, by the time kids reach elementary school they can recognize motivations and consequences of characters’ actions. Kids aren’t going around chucking pitchforks at babies just because we see this in a realistic game.

And a strong argument can be made that watching, playing and participating in activities that depict cruelty or bloodshed are therapeutic. We see the violence on the page or screen and this helps us understand death. We can face what it might mean to do evil deeds. But we don’t become evil ourselves. As Gerard Jones, author of “Killing Monsters: Why Children Need Fantasy, Super Heroes, and Make-Believe Violence,” writes, “Through immersion in imaginary combat and identification with a violent protagonist, children engage the rage they’ve stifled . . . and become more capable of utilizing it against life’s challenges.”

Sadly, this doesn’t prevent lazy journalists from often including in their news reports the detail that suspected killers played a game like Grand Theft Auto. Because the graphic violence of some games is objectionable to many, it’s easy to imagine a cause and effect. As it turns out, a U.S. Secret Service study found that only one in eight of Columbine/Virginia Tech-type school shooters showed any interest in violent video games. And a U.S. surgeon general’s report found that mental stability and the quality of home life — not media exposure — were the relevant factors in violent acts committed by kids.

Besides, so-called dangerous influences have always been with us. As Justice Antonin Scalia rightly noted during the debate, Grimm’s Fairy Tales are extremely graphic in their depiction of brutality. How many huntsmen cut out the hearts of boars or princes, which were then eaten by wicked queens? How many children were nearly burned alive? Disney whitewashed Grimm, but take a read of the original, nastier stories. They pulled no punches.

Because gamers take an active role in the carnage — they hold the gun, so to speak —some might argue that video games might be more affecting or disturbing than literature (or music or television). Yet, told around the fire, gruesome folk tales probably had the same imaginative impact on the minds of innocent 18th century German kiddies as today’s youth playing gore-fests like “Left 4 Dead.” Which is to say, stories were exciting, scary and got the adrenaline flowing.

Another reason to doubt the gaming industry’s power to corrupt: More than one generation, mine included, has now been raised on violent video games. But there’s no credible proof that a higher proportion of sociopaths or snipers roams the streets than at any previous time in modern history. In fact, according to Lawrence Kutner and Cheryl K. Olson, founders of the Center for Mental Health and Media (a division of the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Psychiatry), and members of the psychiatry faculty at Harvard Medical School, as video game usage has skyrocketed in the past two decades, the rate of juvenile crime has actually fallen.

Children have always been drawn to the disgusting. Even if the ban on violent games is eventually deemed lawful and enforced in California, the games will still find their way into the hot little hands of minors. So do online porn, and cigarettes and beer. But these vices haven’t toppled Western civilization.

Not yet, anyway — although a zombie invasion or hurtling meteor might. Luckily, if you’re a good enough gamer, you’ll probably save the day.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, now in paperback.

Picking up steam: Why is Boston the hub of steampunk?

Picking up steam

Mashing modern days with the Victorian age excites role players, artists, and other fans of steampunk

When Bruce and Melanie Rosenbaum bought a 1901 home in Sharon, they wanted to restore it top to bottom. And rather than force a modern interior design, they remodeled it with a Victorian twist.

In the kitchen, an antique cash register holds dog treats. A cast iron stove is retrofitted with a Miele cooktop and electric ovens. In the family room, a wooden mantle frames a sleek flat-screen TV, and hidden behind an enameled fireplace insert, salvaged from a Kansas City train station, glow LED lights from the home-entertainment system.

Unknowingly, the Rosenbaums had “steampunked’’ their home, that is, added anachronistic (and sometimes nonfunctioning) machinery like old gears, gauges, and other accoutrements that evoke the design principles of Victorian England and the Industrial Revolution.

“When we started this three years ago, we didn’t even know what steampunk was,’’ said Bruce, 48. “An acquaintance came through the house and said ‘You guys are steampunkers.’ I thought, ‘Wow, there’s a whole group out there that enjoys blending the old and new.’’

It’s not just the Rosenbaums cobbling together computer workstations from vintage cameras and manual typewriters. Local enthusiasts are mounting steampunk exhibits, writing books, creating objets d’art, and dressing up in steampunk garb for live-action role playing games.

To be sure, steampunk has been part of the cultural conversation for the past several years, as DIY-ers embraced the hand-wrought, Steam Age aesthetic over high-tech gloss. But recently, it seems to be gaining a wider appeal, especially here.

“Boston lends itself to steampunk,’’ said Kimberly Burk, who researched steampunk as a graduate student at Brandeis. “You have the MIT tinkerers, the co-ops in JP, the eco-minded folks.’’

Both a pop culture genre and an artistic movement, steampunk has its roots in 19th- and early-20th-century science fiction like Jules Verne’s “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea’’ and H.G. Wells’s “The Time Machine.’’ Its fans reimagine the Industrial Revolution mashed-up with modern technologies, such as the computer, as Victorians might have made them. Dressing the part calls for corsets and lace-up boots for women, top hats and frock coats for men. Accessories include goggles, leather aviator caps, and the occasional ray gun. And there’s a hint of Sid Vicious and Mad Max in there, too.

Still, steampunk defies easy categorization. It can be something to watch, listen to, wear, build, or read, but it’s also a set of loose principles. Steampunk attracts not only those who dream of alternative history, but those who would revive the craft and manners of a material culture that was built to last.

“The acceleration of the present leaves many of us uncertain about the future and curious [about] a past that has informed our lives, but is little taught,’’ said Martha Swetzoff, an independent filmmaker on the faculty of the Rhode Island School of Design who is directing a documentary on the subject. “Steampunk converses between past and present.’’

It also represents a “push back’’ against throw-away technologies, Swetzoff said, and a “culture hijacked by corporate interests.’’

For Burk, steampunk is more akin to the open source software movement than a retro-futuristic world to escape into. “Steampunk isn’t about how shiny your goggles are,’’ she said. “It’s about how cleverly you create something.’’

The urge to rescue and repurpose forgotten things led the Rosenbaums to spread the steampunk gospel. They’ve founded two companies: Steampuffin and ModVic, which infuse and rework 19th-century objects and homes with modern technology. They’re working on a book about the history of steampunk design. And, hoping some steampunker might want to live in a pimped-out Victorian crib, they purchased a second home in North Attleboro, restored it using their “back home to the future’’ philosophy, and put it on the market.

Bruce is also curating two steampunk exhibits. One will be displayed at Patriot Place’s new “20,000 Leagues’’ attraction, an “hourlong, walk-though steampunk adventure,’’ scheduled to open in December, according to creator Matt DuPlessie.

Meanwhile, “Steampunk: Form and Function, an Exhibition of Innovation, Invention and Gadgetry’’ recently opened at the Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation in Waltham, a former textile mill already filled with steam engines and belt-driven machines.

“Form and Function’’ includes a juried show of steampunked objects (many by local artists) like a steam-electric hybrid motorcycle called “the Whirlygig,’’ an electric mixer powered by a miniature steam engine, and a flash drive made with brass, copper, and glass. Perhaps the most impressive piece is a rehabbed pinball machine whose guts look like Frankenstein’s lab — down to the colored fluids bubbling through vintage glass tubes.

“I like giving things a new life,’’ said Charlotte McFarland of Allston, exhibiting her first-ever steampunk creation, “Spinning Wheel Generator.’’

Such functional art objects tap into a nostalgia for a mechanical, not electronic, age. Unlike the wireless signals, microwaves, and motherboards of today, the 19th century’s gears, pistons, and tubes were visible and visceral. While the workings of a laptop can seem impenetrable, we can fathom the reality of moving parts.

“As the world becomes more digital, the world less and less appreciates machines, which will be lost,’’ said Elln Hagney, the museum’s acting director. “We are trying to train a new generation to appreciate this and keep these machines running.’’

Some of the most committed local steampunkers dress up in period garb and take part in live-action role playing games. Most “LARPs’’ (think Dungeons & Dragons but in costume) are swords and sorcery-based, but Boston’s Steam & Cinders is one of only a couple of steampunk-themed LARPs anywhere.

Once a month, some 100 players gather for a weekend at a 4-H camp in Ashby. The game’s premise? A crashed dirigible has stranded folks at a frontier town called Iron City, next to a mysterious mine. Engineers, grenadiers, and aristocrats vie for supremacy. There are plenty of robots to fight (players dressed in cardboard costumes sprayed with metallic paint), and potions to mix (appealing to the mad scientist in us all). Players stay in character for 36 hours straight.

“Yes, it’s a fantasy world and it’s not England,’’ said Steam & Cinders founder Andrea DiPaolo of Saugus. “But getting to dress in British garb and speak in a British accent is something I enjoy.’’

Meanwhile, publishers are striking while the steampunk iron is hot.

“We can tap into the enthusiasm of a reader who can imagine an alternative version of the 19th century,’’ said Cambridge resident Ben H. Winters, author of this summer’s mash-up book “Android Karenina.’’

Winters steampunked Tolstoy’s novel by re-envisioning Anna Karenina in a 19th-century Russia with robotic butlers, mechanical wolves, and moon-bound rocket ships. Sample line: “When Anna emerged, her stylish feathered hat bent to fit inside the dome of the helmet, her pale and lovely hand holding the handle of her dainty ladies’-size oxygen tank . . .’’

“Hopefully,’’ explained Winters, who also wrote 2009’s “Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters,’’ “we’ll be adding to the fandom of the mash-up novel by introducing a new fan base: the sci-fi crowd.’’

Climb to Bruce Rosenbaum’s third-floor study and you feel as if you’ve entered one of those mash-ups. The attic space feels like a submersible, packed with portholes, nautical compasses, and a bank vault door. His desk is ornate and phantasmagorical, ringed with pipes from a pipe organ. It’s a place where you can imagine Captain Nemo banging out an ominous dirge.

“There’s freedom with steampunk,’’ Melanie added. “Almost anything goes.’’

+++++++

A Steampunk Primer

Not sure who or what put the punk into steam? Here’s a quick-and-dirty intro to some of the culture’s roots and most influential works, plus ways to connect to the steampunk community.

Books

Jules Verne: “From the Earth to the Moon” (1865), “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea” (1869)

H.G. Wells: “The Time Machine” (1895), “The War of the Worlds” (1898), “The First Men in the Moon” (1901)

K.W. Jeter : “Morlock Night” (1979)

William Gibson and Bruce Sterling: “The Difference Engine” (1990)

Paul Di Filippo: “Steampunk Trilogy” (1995)

Philip Pullman: “His Dark Materials” trilogy (1995-2000)

Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill: “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” (comic book series, 1999)

Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, editors: “Steampunk” (2008)

Dexter Palmer : The Dream of Perpetual Motion (2010)

Movies and TV

“20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” (1954)

“The Wild Wild West” (TV series: 1965–1969); “Wild Wild West” (movie: 1999)

“The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” (2003)

“Steamboy” (anime film: 2004)

“Sherlock Holmes” (2009)

“Warehouse 13” (TV series: 2009-)

Steampunk info/community on the web:

The Steampunk Empire: The Crossroads of the Aether, thesteampunkempire.com

Steampunk magazine, steampunkmagazine.com

“Steampunk fortnight” blog, tor.com/blogs/2010/10/steampunk-fortnight-on-torcom

The Steampunk Workshop, steampunkworkshop.com

Other resources:

computer/console games: Myst (1993); BioShock (2007)

Templecon convention (Feb 4-6, 2011; Warwick, RI), templecon.org

Steam & Cinders live-action role-playing game (Boston), be-epic.com

Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation (Waltham, MA), crmi.org (“Steampunk: Form and Function” exhibit through May 10; Steampunkers “meet up” Dec. 19; steampunk course March, 2011; New England Steampunk Festival April 30-May 1, 2011)

Steampuffin appliances and inventions and ModVic Victorian and steampunk home design (Sharon, MA), steampuffin.com, modvic.com

--- Ethan Gilsdorf

When literary authors slum in genre

There’s a curious phenomenon happening out there in LiteraryLand: The territory of genre fiction is being invaded by the literary camp.

There’s a curious phenomenon happening out there in LiteraryLand: The territory of genre fiction is being invaded by the literary camp.

While it could be argued that literary writers have always borrowed from fantasy, science fiction and horror, even stolen genre's best ideas, I think there's a new and significant shift happening in the past few years.

Take Justin Cronin, writer of respectable stories, who recently leaped the chasm to the dystopian, undead-ridden realm of Twilight. With The Passage, his post-apocalyptic, doorstopper of a saga, the author enters a new universe, seemingly snubbing his former life writing “serious books” like Mary and O’Neil and The Summer Guest, which won prizes like Pen/Hemingway Award, the Whiting Writer’s Award and the Stephen Crane Prize. Both books of fiction situate themselves solidly in the camp of literary fiction. They’re set on the planet Earth we know and love. Not so with The Passage, in which mutant vampire-like creatures ravage a post-apocalyptic U.S. of A. Think Cormac McCarthy’s The Road crossed with the movie The Road Warrior, with the psychological tonnage of John Fowles’ The Magus and the “huh?” ofThe Matrix.

Now comes Ricky Moody, whose ironic novels like The Ice Storm andPurple America were solidly in the literary camp, telling us about life in a more-or-less recognizable world. His latest novel, The Four Fingers of Death, is a big departure, blending a B-movie classic with a dark future world. The plot: A doomed U.S. space mission to Mars and a subsequent accidental release of deadly bacteria picked up on the Red Planet results in that astronaut’s severed arm surviving re-entry to earth, and reanimating to embark on a wanton rampage of strangulation.

And there’s probably other examples I’m forgetting at the moment.

So what’s all this forsaking of one’s literary pedigree about?

It began with the flipside of this equation. It used to be that genre writers had to claw their way up the ivory tower in order to be recognized by the literary tastemakers. Clearly, that’s shifted, as more and more fantasy, science fiction, and horror writers have been accepted by the mainstream and given their overdue lit cred. It’s been a hard row to hoe. J.R.R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, Philip Pullman and others helped blaze the trail to acceptance. Now these authors have been largely accepted into the canon. You can take university courses on fantasy literature and write dissertations on the homoerotic subtext simmering between Frodo and Sam. A whole generation, now of age and in college, grew up reading (or having read to them) the entire oeuvre of Harry Potter. That’s a sea change in the way fantasy will be seen in the future—not as some freaky subculture, but as widespread mass culture.

Yes, Margaret Atwood and Doris Lessing have delved into genre, although their works (A Handmaid's Tale, for example) was always taken as highbrow. Perhaps a better example: Stephen King, considered a hack horror writer for years who began publishing in the New Yorker in 1990. One wonders why the New Yorker finally caved and let him in the doors --- is this an implicit acknowledgement of his popularity? Or had King's writing gotten better. In any case, it's was a shocker when he began racking up impressive literary kudos, like in 2003 when the National Book Awards handed over its annual medal for distinguished contribution to American letters to King. Recently in May, the Los Angeles Public Library gave its Literary Award for his monstrous contribution to literature.

Now, as muggles and Mordor have entered the popular lexicon, the glitterati of literary fiction find themselves “slumming” in the darker, fouler waters of genre. (One reason: It’s probably more fun to write.) But in the end, I think it’s all about call and response. Readers want richer, more complex and more imaginative and immersive stories. Writers want an audience, and that audience increasingly reads genre. Each side—literary and genre—leeches off the other. The two camps have more or less met in the middle.

One wonders who’s going to delve into the dark waters next—Philip Roth? Salman Rushdie? Toni Morrison? Actually, it turns they already (sort of) have --- Roth explores alternative history in The Plot Against America;

Rushdie's "Magical Realism," of Midnight's Children, in which children have superpowers. You might even argue that Morrison's Beloved is a ghost story.

[thanks to readers at Tor.com, where this post originally appeared, for catching some errors and helping me revise this into a better essay]

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, which comes out in paperback in September. Contact him through his website,www.ethangilsdorf.com

Top 10 Science Fiction Movie Quotes

Top 10 Science Fiction Movie Quotes

By Ethan Gilsdorf

Science fiction movies voice our fear of what may come to pass if we don't clean up our act (death, destruction, apocalypse), and express our hope for a good life here on planet earth (or other planets) should we choose the right path. In other words, SF can inspire strong opinions about the future of the human race. It can even and create belief systems as powerful as religion. Just look at L. Ron Hubbard.

When I was a kid, instead of quoting Bible passages for spiritual guidance, sometimes my family quoted Star Wars. Imagine the scene in my chaotic house: sink overflowing with dishes, something burning on the stove, dogs tearing apart a trash bag, cats pooping in the basement. The only logical response was to shout, "3PO! 3PO! Shut down all the garbage mashers on the detention level!" (Hence my paranoia about technology, too.) Reciting lines from Episode IV didn't necessary solve my family problems, but it did provide comic counterpoint.

Plus, the Force seemed as plausible an explanation for how the universe hung together as other ideologies and philosophies that had reached the backwoods of rural New Hampshire. In fact, fictional characters like Yoda, Darth Vader, Hal 9000, E.T. felt as real to me as anything else. Raised on monster movies and cineplex fare, I happily let their words infect my brain. I know they've corrupted yours.

But which lines of SF movie dialogue have reached mythic status? Which ones that truly made a permanent stain on our cultural fabric? In my search for the best, most indelible SF movie quotes ever, here was my criteria. 1) They had to be memorable. 2) They had to show staying power over the years. 3) And they had to lines you and I use in everyday life to punctuate our humdrum lives with irony, drama, and humor. (Oh, and number 4: they had to appear in a SF movie, not TV show or book.)

In my humble opinion, here are the ten best. I expect you might quibble with my picks, but heck, that's what these lists are all about. To paraphrase one famous movie line, the more I tighten my grip on this top ten list, the more quotes will slip through my fingers.

(Tune in for my next post, my choices for the Top 10 Fantasy Movie Quotes)

10) "Klaatu barada nikto" --- The Day the Earth Stood Still

In the 1951 SF classic The Day the Earth Stood Still, "Klaatu barada nikto" are the secret words Klaatu (Michael Rennie) passes on to Helen Benson (Patricia Neal). One of the most famous commands in all of SF, the three words are a kind of failsafe code that keeps the robot Gort from destroying the Earth. Good to know. Memorization of this should be required along with the Pledge of Allegiance, your mommy's and daddy's address, and the Lord's Prayer --- just in case.

9) "I'm sorry, Dave. I'm afraid I can't do that." --- 2001: A Space Odyssey

In the 1968 Stanley Kubrick film (based on the novel by Arthur C. Clarke), there's a mission to Jupiter, and the super-smart HAL 9000 computer, seeing that the humans might blow it, begins to off the crew members one by one. Dave Bowman heads out for a spacewalk to rescue his buddy, but HAL locks him out. Bowman: "Open the pod bay doors, HAL." HAL: "I'm sorry, Dave. I'm afraid I can't do that." HAL's passive monotone makes me wonder if there was ever a creepier line said by a computer.

8) "I've seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser gate. All those moments will be lost in time... like tears in rain... Time to die." --- Blade Runner

Replicant Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) waxes poetic to Decker (Harrison "Am I a replicant, too?" Ford), to the dreamy score by Vagelis in one of most bittersweet lines from SF. Then a pigeon or dove flies off into the rare blue sky of rainy cyber-punk Los Angeles, circa 2019 and, I swear, nary a geek in the house can escape with dry eyes.

7) "Doo-Do-DOO-Do-DUMMM" --- Close Encounters of the Third Kind

This isn't technically a line of dialogue, it's a few bars of music (I'm stretching the category here), but heck, when I saw Close Encounters of the Third Kind in the theater back in 1977 and that big mother ship landed on Devil's Tower and began to play "Name that Tune" with the scientists, the musical orgasm blew my mind. I was 11 at the time and I never looked at the night sky the same.

6) "Get away from her, you bitch!” – Aliens

Yes, James Cameron has a mother complex. In the ultimate fem-smack-down, Ellen Ripley makes her grand re-entrance to protect the little feral girl Newt, clomping in the hydraulic crab forklift walker thing to take on the baddest momma alien of all. Aliens (1986) was either a giant leap forward (or backward?) for feminism and science fiction.

5) "Take your stinking paws off me, you damned dirty ape!" --- Planet of the Apes

As George Taylor, Heston gets to utter this, the first words ever spoken by a human to the apes. It may be 1968 in the real world (sexual revolution, student protests, that sort of thing), but in Charlton Heston's world, the poor guy's trapped on an f-ed up planet run by apes. Now, wait a minute --- either this is way, way in the future ... or way, way in the past. Are the apes hippies? Do they belong to the NRA? Either way, don't mess with Heston.

4) "The needs of the many outweigh ... the needs of the few... Or the one." --- Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan

(sorry, can't find a video clip; can anyone find it?)

I know you wanted me to pick Kirk's line, "KHAAANNNN!" But when Spock sacrifices himself (by entering the irradiated zone that's part of the Enterprise's warp drive system and fixing the main reactor just in time), another great SF line was born. The quote is actually tag-teamed by Shattner and Nimoy, each on one side of a transparent barrier. Spock says, "Do not grieve, Admiral. It is logical. The needs of the many outweigh ..." to Kirk adds, "the needs of the few," and Spock ends with: "Or the one ... " Sniff! (Don't worry, Spock won't be dead for long.)

3) "E.T. phone home" --- E.T.

You've said it. I've said it. Say no more. Enough said.

2) "I'll be back" --- The Terminator

Before the Governator was in charge of California, he had another deadly mission: to travel back in time to 1984 to kill Sarah Connor (maybe he could have killed Huey Lewis and the News instead?). Of course, in later Terminator movies, Schwarzenegger got all warm and fuzzy and was on the side of good. This is SF movie quote that is probably repeated (to the annoyance of girlfriends and wives everywhere) more than any other.

1) " Do... or do not. There is no try." – The Empire Strikes Back

Many of us who originally saw the 1980 film fondly remember this scene in the swamps of Dagobah featuring the grumpy and whiny student, Luke Skywalker, and his impatient, diminutive, Kermit the Frog-like teacher, Yoda. Whiny Luke can't get it up (no, not that – the "it" is an X-wing sunken in the). Yoda, the Zen master, Luke: "All right, I'll give it a try." Yoda: "No. Try not. Do... or do not. There is no try." And with such few words, a green rubber puppet inspired an entire generation, and made us believe in forces we can't see or understand.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of the travel memoir / pop culture investigation Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms. More information at http://www.ethangilsdorf.com

Avatar is about transformation

PSAs from the future

No explanation needed. Just watch 'em.

No explanation needed. Just watch 'em.

--- Ethan Gilsdorf, author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks