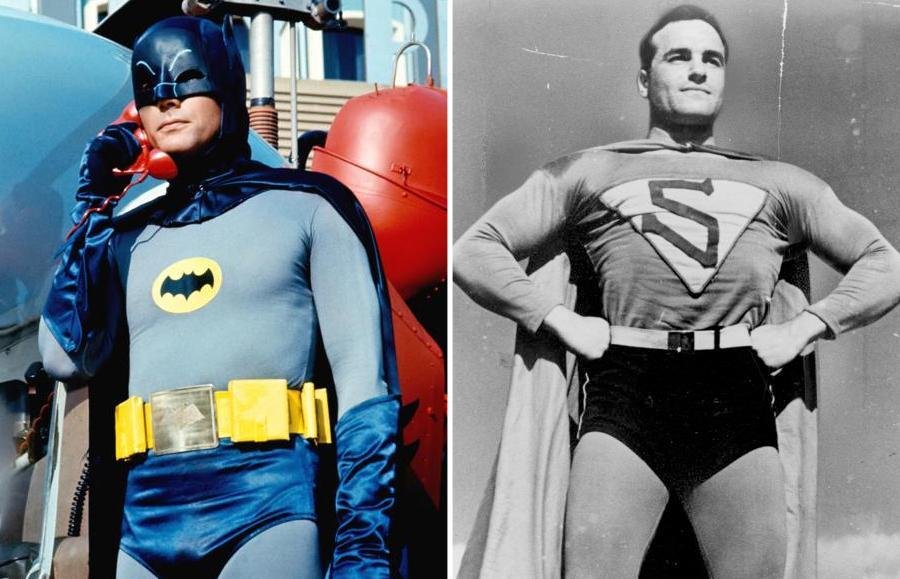

Batman vs. Superman Smackdown!

In this 3-parter in The Boston Globe, I give you (almost) everything you wanted to know about Batman and Superman, in advance the new “Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice" movie, including: 1) a look at the new movie in the context of previous Batman and Superman films (and if Affleck is up to the task of being the Caped Crusader); 2) an overview of “Batman and Superman at the movies” and 3) a Batman/Superman fact sheet.

In this 3-parter in The Boston Globe, I give you (almost) everything you wanted to know about Batman and Superman, in advance the new “Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice" movie, including: 1) a look at the new movie in the context of previous Batman and Superman films (and if Affleck is up to the task of being the Caped Crusader); 2) an overview of “Batman and Superman at the movies” and 3) a Batman/Superman fact sheet.

Product placement in the National Parks

It’s been said by more than Ken Burns that the national parks are America’s best idea. In “National Parks Adventure,” opening at the Museum of Science’s Mugar Omni Theater on Friday, narrator Robert Redford makes the same claim. But after this hokey and commercialized IMAX road trip, you’ll be thinking the best idea might have been to stay at home. Read the rest of my Boston Globe review.

Geek out in the Galapagos

Sometimes, we watch a documentary to be sucker-punched by its investigative uppercut. Other times, it’s to be awed by nerdy info and eye-candy. The IMAX science museum/aquarium movie “Galapagos 3D: Nature’s Wonderland" may not be subtle or particularly brilliant. But this science-y doc sates that second desire just fine. Read the rest of my review of “Galapagos 3D: Nature’s Wonderland" for the Boston Globe.

Dune is in Your Head

If you've ever seen the 1984 David Lynch film version of Dune, or the three-part TV mini-series from 2000, you know that both adaptations of Frank Herbert's classic sci-fi novel left plenty of his world on the cutting room floor --- and left something to be desired.

If you've ever seen the 1984 David Lynch film version of Dune, or the three-part TV mini-series from 2000, you know that both adaptations of Frank Herbert's classic sci-fi novel left plenty of his world on the cutting room floor --- and left something to be desired.

But what if there was one version of Dune that would have blown the minds of critics before they had a chance to grumble?

In this story for BoingBoing, "Dune is in Your Head: The mirage of Jodorowsky’s Unfilmed Epic," I delve into the history of director Alejandro Jodorowsky's version of Dune, the one that was never made, and the one now captured in a terrific documentary called Jodorowsky's Dune.

Below, a couple of the production stills from the never realized film.

Concept art by Swiss artist H.R. Giger. All photos courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

Concept art by Swiss artist H.R. Giger. All photos courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

Storyboard of Dune, art by Jean Giraud, aka French comic book artist Moebius(Photo: David Cavallo) All photos courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

Storyboard of Dune, art by Jean Giraud, aka French comic book artist Moebius(Photo: David Cavallo) All photos courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

How about some edgier Muppet movies?

A post about possible alternative Muppet movies, from “The Muppets’ Rings of the Lord” and “The Muppets’ End of the World” to “The Muppets Go Psycho” and “The Muppets Greatest Story Ever Told.” You might have better ideas.

I enjoyed putting together this post about possible alternative Muppet movies, from “The Muppets’ Rings of the Lord” and “The Muppets’ End of the World” to “The Muppets Go Psycho” and “The Muppets Greatest Story Ever Told.” You might have better ideas.

I enjoyed putting together this post about possible alternative Muppet movies, from “The Muppets’ Rings of the Lord” and “The Muppets’ End of the World” to “The Muppets Go Psycho” and “The Muppets Greatest Story Ever Told.” You might have better ideas.

... what if these puppets explored other Hollywood tropes and genres—more risky ones at that? There’s some slim precedent for this frog’s leap into more adult themes: The Muppets took on the Seven Deadly Sins and other more prurient themes in a weird 1975 TV special called “The Muppet Show: Sex and Violence.”

Read the rest on WBUR's The ARTery

A 2006 Interview with Ralph Bakshi

Bakshi in the 1970s.

Speaking of unearthed treasures from the past, I just unearthed this 2006 interview I did with legendary experimental animator Ralph Baskhi.

Bakshi in the 1970s.

Speaking of unearthed treasures from the past, I just unearthed this 2006 interview I did with legendary experimental animator Ralph Baskhi. I recently wrote about him in connection with new, unearthed footage from his Lord of the Rings adaptation.

I hope you enjoy.

Ralph Bakshi in 2009 (Wikimedia Commons)Speaking of unearthed treasures from the past, I just unearthed this 2006 interview I did with legendary experimental animator Ralph Baskhi. I recently wrote about him in connection with new, unearthed footage from his Lord of the Rings adaptation. I hope you enjoy.

Ralph Bakshi in 2009 (Wikimedia Commons)Speaking of unearthed treasures from the past, I just unearthed this 2006 interview I did with legendary experimental animator Ralph Baskhi. I recently wrote about him in connection with new, unearthed footage from his Lord of the Rings adaptation. I hope you enjoy.

An interview with Ralph Bakshi

by Ethan Gilsdorf

[November 2006]

Ralph Bakshi, pioneer of trippy, controversial cartoons with adult themes, has always been able to make films on the cheap. But lately, Bakshi has learned frugality doesn't open doors in Hollywood. Nor does the title 'legendary independent animator': Bakshi hasn't been able to get studios interested in his latest project, the "The Last Days of Coney Island," budgeted at a mere $5 million.

Yet computers may save him. For Bakshi, the promise of low-cost technology is that it could allow outsider animation to rise again. His new Bakshi School of Animation and Cartooning, based in Silver City, New Mexico, teaches a hybrid of old techniques: hand-drawn 2-D, processed in computers using relatively inexpensive software like Toon Boom.

Ralph Bakshi was born in October 1938 in Haifa, Israel. In 1939 his family came to New York escaping the war. He grew up in Brooklyn and went to the High School of Industrial Arts, now called High School of Art & Design. His first animation job was with Terrytoons Animation Studios, where he upset the status quo by becoming an animator on Mighty Mouse and Heckle & Jeckle shorts without working his way up the ranks. He started his own production company in the late 1960s, and in 1972 he finished his first feature, "Fritz the Cat,' the first cartoon ever given an X-rating.

He went on to direct 'Heavy Traffic' (1973), which screened at the Museum of Modern Art. With this film he began his trademark mix of live action, animation, and animating characters against a backdrop of still photos, a technique continued in the controversial 'Coonskin' (1975). 'Wizards' (1977) was his first film extensively using rotoscoping (using live footage as a guide for animation). 'The Lord of the Rings' (1978), 'American Pop' (1981) and 'Fire and Ice' (1983) were his last major works before returning to TV and 'Mighty Mouse' shorts in the late 1980s. But a frustrating battle with Hollywood over 'Cool World' (1993) began his disenchantment with full-length production.

He went on to direct 'Heavy Traffic' (1973), which screened at the Museum of Modern Art. With this film he began his trademark mix of live action, animation, and animating characters against a backdrop of still photos, a technique continued in the controversial 'Coonskin' (1975). 'Wizards' (1977) was his first film extensively using rotoscoping (using live footage as a guide for animation). 'The Lord of the Rings' (1978), 'American Pop' (1981) and 'Fire and Ice' (1983) were his last major works before returning to TV and 'Mighty Mouse' shorts in the late 1980s. But a frustrating battle with Hollywood over 'Cool World' (1993) began his disenchantment with full-length production.

Bakshi spoke via telephone from Silver City, New Mexico. Among the many issues on his mind was the future of outspoken and edgy animation in the United States.

Ethan Gilsdorf: It seems that independent, feature-length animation for adults doesn't even it exist any more.

Ralph Bakshi: I have a very strong feeling about that. First of all, it's very complicated. The companies that are doing animated films right now are very huge companies. They have lots of money invested in technology. They spend so much money on their films that have to make huge grosses to make back their investment. A guy like me is very dangerous to them.

Gilsdorf: My sense of full-length animation is it's booming, but it's all being marketed to kids, other than films like 'Corpse Bride,' 'Nightmare before Christmas,' and 'Final Fantasy' (which is based on video game). Other than foreign films like 'The Triplets of Belleville,' animation for adults is really just special effects sequences in live action fantasy/sci fi/adventure movies.

Bakshi: Tim Burton is naturally making films his way. He's being very true to himself. That's his style of humor. But he gets to make the films because his other films are so successful. Tim Burton worked with me on 'Lord of the Rings.' It was his first job out of college, I hired him. He used to paint cels. He's being very honest as a filmmakers; he's not making what people want to see. He's making what he wants to see. But you go to Hollywood and mention Tim Burton in relation to Ralph Bakshi and people will say, 'Well that's Tim Burton.' I liked 'Triplets of Belleville.' I'm using more live action than 'Belleville' [in the 'Last Days of Coney Island'].

Gilsdorf: How have you adapted to the new climate?

Bakshi: I went out the Hollywood a couple of years ago. I thought, my budget was $5 million, I could go anywhere. I thought it was a slam dunk. They all wanted me to get involved in computer animated films. But no one would dare to buy it ['The Last Days of Coney Island']. I had about eight minutes of film and a completed script. I thought budget was a slam dunk. For a Bakshi comeback film, it seemed like a no-brainer. I tried for about a year. The structure of Hollywood had become very strong there was no way in. My freedom I had in the 1970s I took for granted. [Today, it's all the] business approach to animation. No one wants to do anything else. I could become a threat if I could make a profit with a $5 million film. I grew up feeling like a $30 million gross was a lot of money. It IS a lot of money [he laughs like a cartoon character]. I come from the old school. If you make $5 million profit that was a lot of money.

Bakshi in the 1970s.

Bakshi in the 1970s.

[Hollywood] doesn't have the same business [system] as I was when a young man. With 'Coney Island,' the budget was still low. I asked one guy, should I have a budget of $150 million and pocket the rest? He said yeah, but you have to make [the movie] PG.

Gilsdorf: Sounds like a real attitude change. It's all about the money now.

Bakshi: Who runs these companies? I grew up being animator, Disney grew up as an animator. I grew up at time when the man who ran the animation company was a animator. He had hands in a production background. [These days] these companies are all run by people who don't have a production background.

Gilsdorf: This recent Hollywood experience must have changed your outlook on making animated features.

Bakshi: What they'd done is taken a lot of freedom away from me, from filmmakers who want to make personal films. [So] I went back to painting and drawing. I'm still doing film, slowly.

Gilsdorf: Do you think the digital revolution will help your comeback?

Bakshi: Everyone wants to do computer animation. It's not because I'm against it, I just don't want to do it. I don't think any one style is the answer to any film. One style doesn't stop the other. Computers don't kill hand drawn film. It's just a technique, a preference. It's like saying acrylic paint is going to kill oil paint.

Gilsdorf: What do you think of CGI techniques?

Bakshi: I saw 'War of the Worlds.' I think what they're doing with special effects is amazing. It's very close to magic. Let's not confuse my personal taste in animation with special effects in motion pictures. When an entire building collapses and explodes [as in 'War of the Worlds'], and thousands of men in armies attacks each other [like 'The Lord of the Rings'], that's amazing. I just don't think that's for animation.

Gilsdorf: And your opinion of digital rotoscoping like in 'A Scanner Darkly' and 'Waking Life,' by Richard Linklater?

Bakshi: I don't want to talk about it. I don't want to put the guy down. The guy's trying. I gave up on rotoscope because I don't like it. I don't want to do that look. It's cold. It's lifeless, and it has no heart. I much prefer hand drawn, like Fleischer, I like using hand drawn techniques.

Gilsdorf: Tell me how qualitatively the two techniques, hand-drawn versus digital, are different.

Bakshi: Say my character is in a subway. I'll use a real shot of an elevated subway going by up above. And I'll doctor it, color it. It's like an animated character is living in a real world. I have real animation. You get all the shadows that are real, that they're not rendered. It's the same technique I used in 'Coonskin' and 'Heavy Traffic.' I am not using rotoscope. I think it takes the fun away from the stories I want to tell.

Bakshi: Say my character is in a subway. I'll use a real shot of an elevated subway going by up above. And I'll doctor it, color it. It's like an animated character is living in a real world. I have real animation. You get all the shadows that are real, that they're not rendered. It's the same technique I used in 'Coonskin' and 'Heavy Traffic.' I am not using rotoscope. I think it takes the fun away from the stories I want to tell.

Gilsdorf: But rotoscoping also has its benefits. It saved you time and money, in films like 'Wizards' and 'Lord of the Rings.'

Bakshi: If you do adult animation, you have to have a sense of believability. Using live action had that sense, with rotoscoping, like in 'Heavy Traffic.' [But] I used to have to have hundreds of people to make [those effects] happen, all the labor, the optical house fees.

Gilsdorf: So, yes, aren't there are benefits to computer animation, in terms of cost, economy of scale?

Bakshi: [Software like] Toon Boom has a lot more choices, one thousand percent more choices, for a fraction of the cost. I had a studio in a box. Everything I used to spend millions of dollars on I could do for nothing. I could do a film like 'Heavy Traffic' for a one hundred percent better quality for a tenth the cost. You get shadows [all these effects]. I was amazed. I went crazy.

Gilsdorf: So, let's say you can get the money. Is there still a market for films like the ones you made in the 1970s and 1980s?

Bakshi: The audiences want something different. If you're looking at one type of movie all the time, a computer generated film, it gets boring. If I was looking at say $90 million to make a film with adult themes, that would be chancy. But if you make a $5 million Bakshi film I don't see that as risky. It seems like a slam dunk. 'Fritz the Cat' was a hit [because it was the right film at the right time]. I can make $30-40 million profit on a film. I can't see how they can turn me down. I'm still very puzzled by it. I don't know what the truth is. I don't know how people can turn it down when adult comics, adult cartoons, all are doing very well, 'The Simpsons,' for 15 years on TV, it's been doing very well. 'Adult Swim' is doing very well.

Gilsdorf: And you can make a profit?

Bakshi: My original version of 'The Lord of the Rings' made $90 million. Saul Zantez also produced the second. The original film was a smash hit, compared to the $8 million that it cost to make it.

Gilsdorf: And your fans, where have they gone to? You haven't really made a film, that was totally yours, since 'Fire and Ice' in 1983.

Bakshi: I don't want to blow my own horn, but I'm getting more emails, more letters, I'm selling more DVDs, to 18, 20 year olds. They are all discovering my films. The fan following around the world is so huge. People are re-discovering my film. Cels from film my wife sells at $250-$500 a piece. That's what funding my films. You can go to any college and people know what a Bakshi film is. I was stunned. But I thought I had failed. Artists, want to leave something behind.

Gilsdorf: What did you think your legacy was?

Bakshi: When I quit the biz, I felt defeated, I felt tired. But [now] I feel very vindicated. I get hundreds of emails from kids all over the world, Russia, China, Japan, about 'Heavy Traffic,' 'Coonskin.' They are amazed that my films exist. I get emails from rappers saying that I had discovered rap music. I like what Kerouac said, 'If you live long enough you get rediscovered.' My films still speak to a new generation of disaffected young people. But you tell me why they [studios] won't buy a movie from me. I can make a low budget film and make a profit a movie company. I have my own fans that aren't dead. I have young fans. And word of mouth. I don't feel bad at all.

Bakshi: When I quit the biz, I felt defeated, I felt tired. But [now] I feel very vindicated. I get hundreds of emails from kids all over the world, Russia, China, Japan, about 'Heavy Traffic,' 'Coonskin.' They are amazed that my films exist. I get emails from rappers saying that I had discovered rap music. I like what Kerouac said, 'If you live long enough you get rediscovered.' My films still speak to a new generation of disaffected young people. But you tell me why they [studios] won't buy a movie from me. I can make a low budget film and make a profit a movie company. I have my own fans that aren't dead. I have young fans. And word of mouth. I don't feel bad at all.

Gilsdorf: So what is the next chapter in the Bakshi story?

Bakshi: I don't have the fire in my belly to run around the world and raise money. It's a lifestyle choice. I'm 68. I'm counting on guys like you [the jjournalists]. Someone will read this, some producer might say, 'I might take a chance.' I'm not running around Hollywood embarrassing myself. I will continue to putter around on my film until I finish it, or I won't finish it. I'm not going back to Hollywood. It was too embarrassing, it was a hard pill to take.

Everyone wanted my autograph to give to their kid. It's disheartening when you're someone my age. The '70s, the days of truly independent filmmaking were better than I ever knew. Can you believe what's going on out there in the world? It's crazy. Global warming, war. Even more reason to do adult themes. You've got to start facing what's going on. What does it take for Hollywood to take a chance? I think there's a huge audience for adult animated films. Maybe if one came out, maybe someone would call me.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of 'Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms." He publishes arts, pop culture and travel stories, essays and reviews regularly in the New York Times, Boston Globe, Salon.com, as well as BoingBoing and PsychologyToday.com, and contributes regularly to Boston NPR affiliate WBUR's Cognescenti blog.

A review of RoboCop 2014: Not as Good as RoboCop 1987

In which I watch RoboCop (2014) and remember RoboCop (1987), and conclude that while the remake isn't without its qualities, it has less to say than the original, and, worse, is not as funny. I also break down the history of our anxiety about robots and A.I., from Metropolis to The Terminator to Her. It's all over at BoingBoing.

Desolation of Tolkien: My BoingBoing review of Smaug

If part 1 plodded, then part 2 flies. But in what directions! And, quite possibly, asunder. Read more of my review of my BoingBoing The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug

If part 1 plodded, then part 2 flies. But in what directions! And, quite possibly, asunder. Read more of my review of my BoingBoing The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug

A travel guide to imaginary realms

Time traveling adventurers in Time BanditsA travel guide to imaginary realms

Time traveling adventurers in Time BanditsA travel guide to imaginary realms

How do you get to Narnia, Neverland, Oz, or Hogwarts? The way to these parallel other worlds that sometimes intersect with ours is not always obvious. All you need to know is the secret. Here is a brief guide to common tropes and modes of transportation. When in doubt, try a dash of fairy dust.

Natural (or Unnatural) Phenomena

In “Epic,” it’s a magic flower bud, or “pod,” as well as the spirit of a dying queen, that transports M.K. to the land of the Leafmen. Tornadoes also do the trick, as in “The Wizard of Oz.” Or a whack to the head works, too, like the one the kid in “The Pagemaster” suffers before the fantasy world of the library comes to life.

Tunnels, Caves, and Dark Spaces

Slither into a tunnel or cavern (“Pan’s Labyrinth”), fall down a hole (“Alice in Wonderland”), or explore the back of your closet (“The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe”). By means of this reverse birth-womb experience through the darkness — paging Dr. Freud — you’ll reach that hidden world.

Portals and Hidden Places

What's down that rabbit hole or in that wardrobe? ‘Epic’ follows tradition of children’s fictions bridging earthly, fantasy realms

What's down that rabbit hole or in that wardrobe?: ‘Epic’ follows tradition of children’s fictions bridging earthly, fantasy realms

What's down that rabbit hole or in that wardrobe?: ‘Epic’ follows tradition of children’s fictions bridging earthly, fantasy realms

In the just-opened animated adventure film, “Epic,” a teenage girl named Mary Katherine (voiced by Amanda Seyfried) has effectively been abandoned. She arrives in the country to reconnect with her harebrained dad (Jason Sudeikis), a nerdy scientist obsessed with finding a woodland kingdom of miniature creatures. Grieving the loss of her mother, Mary Katherine, or “M.K.,” needs her father more than ever. But her dad’s belief in a secret world makes him all the more distant. “I’ll be right here,” M.K. huffs. “In reality.”

Naturally, M.K.’s ideas about magical realms are about to change. Stumbling into the woods, she snatches what looks like a glimmering leaf as it drifts down from the trees. The “pod” glows brighter in her hands, and then, KA-POW! our heroine is transported (and shrunk) to the hidden land of the Leafmen. There, she finds her purpose among a race of tiny people who, armed with bows and swords and mounted on sparrows and hummingbirds, protect the forest from the baddies in, yes, an ongoing battle between the forces of good and evil.

Movies about worlds disconnected from our own are commonplace. Think of the many science fiction and fantasy narratives that lie along the “Star Wars” to “The Lord of the Rings” continuum. These separate realities are filled with orcs and wizards, siths and spaceships. Humans may live there, but we Earthlings can’t visit them. No magic door leads from Boston to Tatooine, no trip down a rabbit hole or along the Red Line arrives in Middle-earth.

“Epic” belongs to a different but equally longstanding tradition of fiction that bridges our world to other realms. Via some gateway, a journey is made to a kind of Neverland or Narnia. The trope is as old and dark as the burrow in “Alice in Wonderland” and Dorothy’s twister in “The Wizard of Oz.” You can follow these tunnels from “Labyrinth” to “Pan’s Labyrinth,” through “Harry Potter” and “Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief” and beyond to every story that maps that liminal space between us and some parallel place.

As sophisticated and tech-savvy as we’ve become in the 21st century, apparently we still need to believe in hidden worlds that coexist with the real world. In fact, we might need them more than ever. As we get more attached to our digital devices, our traditional spells don’t work anymore. Satellites have mapped every square inch of the planet; Google conjures an explanation for everything. We’re disconnected from witchcraft, nature, and the mysterious. Myth and fairy story gain no purchase on our daily lives.

Consequently, as we’ve galloped from industrialism to post-industrialism to digitalism, we’ve seen an explosion of fantasy and adventure movies in the last 30 years — from “The Goonies” (1985) to “The Golden Compass” (2007) — which reconnect us to these concealed worlds. We cling to old stories, newly enhanced by advances in special effects whose verisimilitude makes these worlds feel more convincing than ever.

Read the rest of my story at Boston Sunday Globe